You couldn't make it up

In a number of recent blogs, I have highlighted the disparity between what’s actually going on in the economy (despite all of the headwinds) and the apocalyptic versions portrayed by the media. Last week, the Economist was at it in an article entitled, “Britain is slowly going bust”, in which it drones on about sticky inflation (it isn’t), high debts and deficits (they aren’t in the private sector) and yields on long-term government debt that are above peer economies (yes, they are, but given that the Bank of England isn’t issuing any of these long-dated gilts this is somewhat irrelevant). Further on in the uplifting introduction, the Economist then quotes Ray Dalio, a hedge fund manager now based in the UAE, who says that the UK is in a “debt doom-loop.” So, all very cheerful so far. The following sentence then adds that the infrastructure and housing projects that were supposed to be the engine of growth (only to the very naïve) are turning out to be a sorry disappointment.

Like all good works of fiction, this one has a sprinkling of truth in it, but in the round, it is just wrong and adds another opinion to the long list of voices parroting the same consensual message.

More data revisions and their implications

Interestingly, the Economist article was published on the same day the ONS released updated UK economic data in its latest quarterly national accounts publication, which received, as far as I can tell, absolutely no attention whatsoever in the financial media. And here’s why, because it did not fit the doom narrative. In fact, the revised data, along with better-than-expected H1 growth this year and slightly higher inflation, mean that nominal GDP at the end of Q2 2025 was 2.25% bigger than the OBR’s Spring forecast. Yes, to repeat, that’s 2.25% bigger than the OBR’s March 2025 forecast, or an additional £60bn of output.

The table below shows the nominal GDP revisions going back to 2014.

Before commenting on these significant revisions, I will look at what the numbers now imply for the remainder of 2025.

Importantly, growth in the second half of 2024 has been revised up, which means that over the four quarters to June 2025, the UK economy grew by 1.4% in real terms, 0.3% higher than the previous estimate. If the Bank of England’s Q3 2025 forecast of 0.4% growth is accurate, then by the end of Q3, YOY growth will have accelerated to 1.6% and if, as I suspect, Q4 is also half decent, we will exit 2025 having grown by something close to 1.9%. (This is higher than my apparently ludicrously optimistic 1.5% expectation!)

Finally, as we peer into 2026, a year in which consensus has growth slowing to 1%, I am left struggling to see how it can be less than twice that. In fact, an outcome above 2% could be perfectly plausible given that interest rates will be significantly lower throughout the year, which will, in my view, lead to higher household spending and lower savings.

The revisions to nominal GDP shown in the table above were especially interesting to me, given the current debate about the OBR’s forecasts for productivity growth and what that might imply for the fiscal challenges confronting the Chancellor at the end of November.

Looking at the table and the 2024 column, you will see that the ONS has revised down the household sector (spending) but most prominently, has upgraded investment spending by a whopping £42.2bn or about 1.6% of GDP. I thought this was especially interesting for a number of reasons:

- It is yet another reminder that the ONS is struggling to provide accurate data on which appropriate policy decisions can be based. My understanding is that the ONS has also identified a new problem in relation to EU and non-EU trade and has stopped producing this data until an audit of this series is complete.

- Many commentators have been critical of the UK’s lack of investment and have linked this criticism to dire prognostications about UK productivity. This very significant ONS adjustment might, at the very least, cause a moment of reflection on this particular argument. (More on this below)

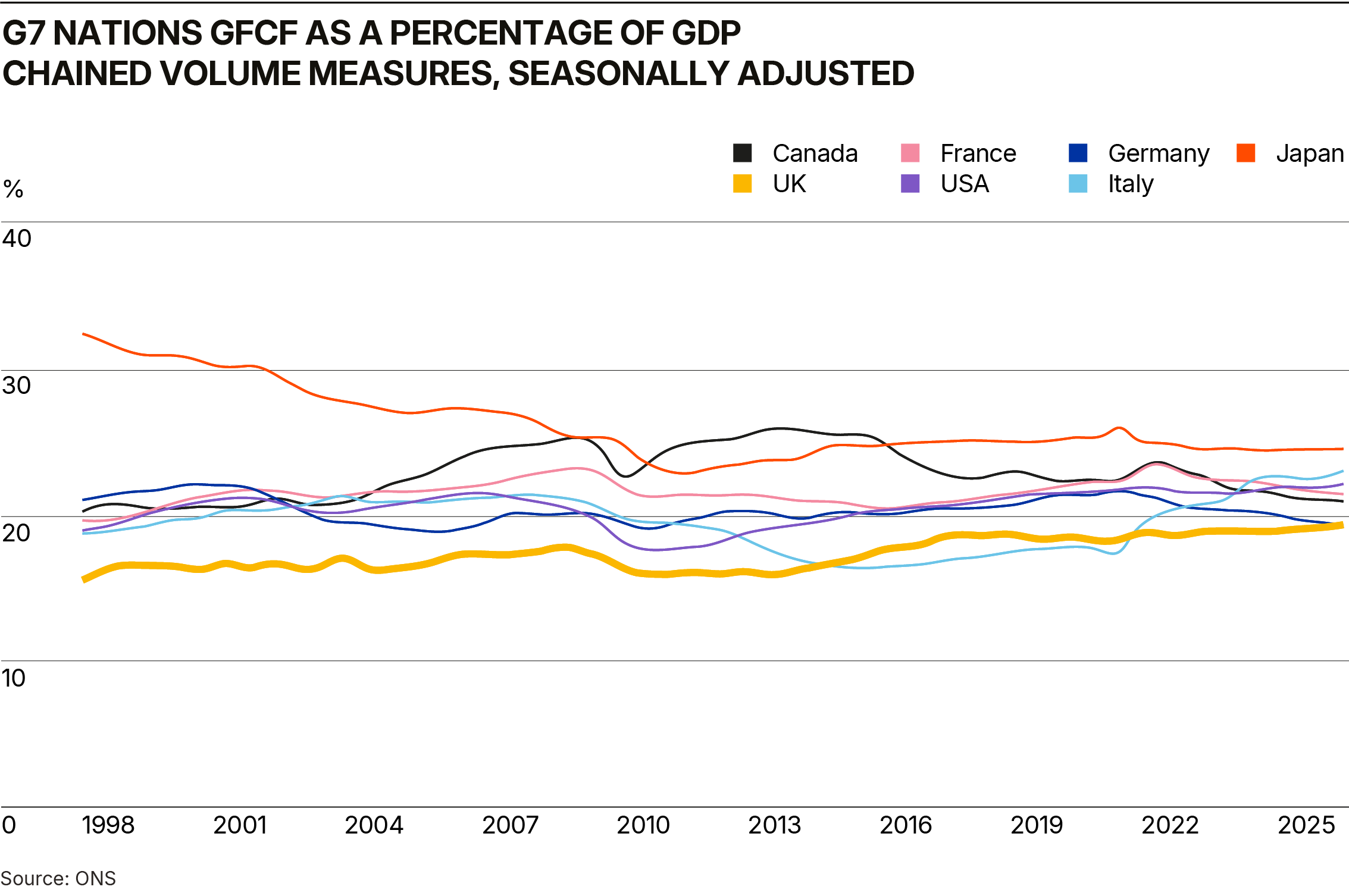

- Commentators have long highlighted the UK’s poor track record on investment, portraying it as an outlier compared with the rest of the G7. Very interestingly, this narrative will now have to be rewritten. Although we do not lead the G7 league table, that place is taken by Japan; the UK is now, following these revisions, above Germany and no longer that far off peer economies that have a higher weighting towards manufacturing. (See below)

In the chart above, Japan leads, followed by Italy, the US, France, Canada, the UK, and finally Germany. The definition of GFCF (gross fixed capital formation) includes public and private investment.

However, I believe there is more to this subject than this basic comparison of raw investment data.

I have written about this before and will highlight it again. I am convinced there is a measurement problem here in the UK, and the data the ONS produces, which commentators base their productivity assertions on, is flawed.

The UK economy has indeed lagged its peers in terms of public and private investment as represented by GFCF in the chart above. However the apparent gap that has previously been used as the explanation for poor productivity outcomes in the UK is now, as a result of this ONS revision, not anything like as big, and may in part, have as much to do with the UK economy’s greater exposure to services than its G7 peers than it has to an imagined systemic problem with investment. Indeed, manufacturing now accounts for just over 8% of the UK GDP, the lowest proportion in the G7. This compares with Japan at 20.6%, Germany at 17.8%, Italy at 14.6%, the US at 10.2%, France at 9.4% and Canada at 9.3%. (Based on OECD and World Bank data)

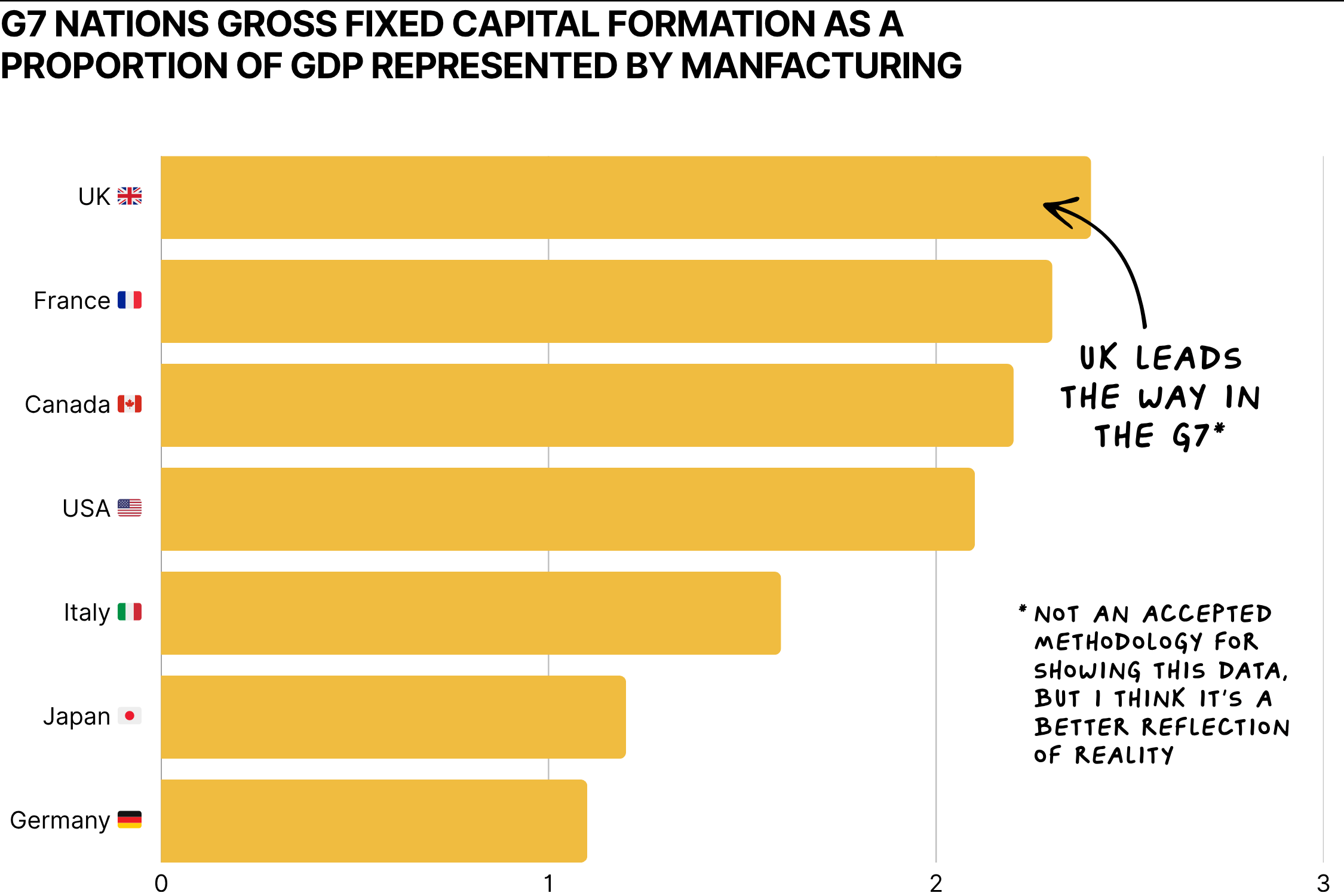

If GFCF were represented in a different way, by dividing it by the % of the economy represented by manufacturing, the results would look very different, with bizarrely, the UK leading the way in the G7. Here are the results of that exercise:

As far as I know, this is not an accepted methodology for presenting this data series. (In fact, I just made it up.) However, I believe it is a better way to compare basic investment data by adjusting it for the different characteristics of the G7 economies.

Having outlined what these data revisions imply, let's put them in the context of the Chancellor’s judgements ahead of November’s budget.

Rachael’s challenges, the OBR and how to avoid stupidity

“The stupid are all around us: they are in every place, in every class, ready to cause damage to others and naturally to themselves. The stupid form the most dangerous category of human beings. Woe betide those who underestimate them.”

– Carlo M. Cipolla

I thought twice about writing this for fear of being seen as arrogant, but such is the basic stupidity of the situation the UK economy confronts right now, I couldn’t resist it.

The UK government, or more precisely, Rachael Reeves and her Treasury team, are currently grappling with the challenge of constructing a budget for November 26th whilst being assailed by a barrage of dire economic forecasts, a consensus narrative that has assumed as fact a fiscal blackhole of between £20 and £35bn, and apparently the near inevitability of an IMF bailout. To some extent, she is a victim of her own making, having embarked on a damaging tax and spend agenda this time last year, combined with her government’s failure to deliver just £5bn of spending cuts from a planned total spend this year of over £1.1trn, or about 44% of GDP. This, of course, followed the explosion of public spending under the Tories during the global pandemic and the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

The Budget-setting process

There is much speculation about what the Chancellor will have to do at the end of November, but none of what is debated would be helpful for the economy. As this government must by now know, higher taxes stifle growth and only make the budget arithmetic even more challenging in the future. The solution to her and the nation’s problems is more growth, not more taxation. Yet, higher taxes are the inevitable result of the self-imposed, self-harming, and profoundly stupid process into which the UK budget-setting process is now locked. This is how it “works”:

- Twice a year, the OBR is legally obliged by the Budget Responsibility and National Audit Act 2011 (eternal thanks must go to George Osborne for this profoundly stupid idea) to produce a detailed five-year forecast for the economy and public finances to coincide with the Autumn Budget and Spring Statement. These forecasts are designed to predict the impact of expected economic developments and government policies on tax and spending.

- Ahead of receiving these detailed forecasts, the Chancellor and her Treasury team look at various policy options, which in the past has included kite flying and speculation, shadowy media briefings, leaks, etc.

- There is then a process of iteration, back and forth with the OBR, which involves them modelling various proposals until agreement is reached and the budget is decided.

- This is then incorporated into the OBR’s musings for its next detailed five-year forecast, which this time around will come only four months after this one is finalised.

This is what I think about the process

Logic and a basic understanding of the world would dictate that a detailed five-year forecast worth its salt would have more than a six-month shelf life. Why the OBR is required to produce two a year is beyond me. If it is a long-term forecast, that is what it should be, and there should be no automatic requirement to start changing it literally a few weeks after the last one has been finalised. Once a year would be more than sufficient.

As I pointed out in a lengthy blog post last year, the OBR's forecasting record is woeful. If the OBR cannot forecast the near-term economy accurately, what credibility should its five-year number enjoy?

Economist David Miles, who sits on the OBR committee, recently said that “productivity forecasts are an educated guess, and maybe not even terribly educated.” Yet, this productivity forecast is pivotal to the OBR’s longer-term forecasts for the economy, which then dictate what the Chancellor has to do in the budget.

Basing fiscal policy adjustments today (or in a few weeks to be precise) on the five-year uneducated educated guesses of an organisation that cannot forecast Christmas is the definition of lunacy. Yet, that is what we confront here in the UK, and it is this lunacy that results in the endless tripe we are assailed with on fiscal black holes and impending IMF bailouts. These only exist in the spreadsheets of those who parrot the doom-laden forecasts of organisations like the NIESR, the IMF, the OECD, and the OBR, whose forecasting record is a collective embarrassment and whose prognostications should never be the basis on which fiscal policy decisions should be made.

There is, of course, a place for independent analysis of the government’s fiscal calculations, but the power now vested in the OBR is the definition of overreach. Its governance structure indicates that it is accountable to an oversight board populated with three internal members and two NEDs. Most interestingly, according to publicly available narrative, the OBR is accountable to Parliament and the Chancellor. So, in effect, it is accountable to the very person whose policy decisions it is obliged to opine on and, in reality, whose fiscal policy decisions it dictates. My guess is that an ex-Prime Minister and Chancellor in the form of Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng would see that accountability somewhat differently, as I imagine would Rachel Reeves.

What would I do?

Having outlined how the OBR is positioned in relation to the fiscal policy decisions we are about to be subjected to, here is my take on what’s happening right now and what I would do if I was advising the Chancellor.

I would argue that basing fiscal policy decisions to be announced on November 26th on the frequently changing, uneducated “educated guesses” of what the OBR thinks will happen to the UK economy over the next five years is the definition of stupidity.

Central to the rumoured changes that the OBR has apparently already decided on is a downgraded view on UK productivity in the next five years (the very thing David Miles said was in effect an uneducated educated guess) This downgrade will in effect lead to a lower medium term growth forecast of about 0.2% pa, which in turn generates in 2029/30 about £15bn less in tax revenue than the OBR forecast back in March. I believe this means that the OBR will downgrade its average growth forecast over that period to about 1.5% pa rather than its March forecast of 1.75% pa.

Quite what has motivated this change is not yet apparent, but I thought it was deliciously ironic that in the week this story emerged, the ONS was forced to upgrade its 2024 growth number (by £33bn, see above table) and, importantly, to upgrade its estimate of 2024 investment spending by a whopping £42.2bn. On top of that, it is now clear that the UK’s nominal GDP at the end of Q2 this year was 2.25% higher than the OBR forecast in March. So, just as the OBR is about to tell the Chancellor that lower productivity in the next five years will mean that she will have to increase taxes, it is being forced to upgrade its contemporaneous calculation of UK productivity.

Thinking about forecasting

If I were in the business of forecasting UK productivity over the next five years, I would be thinking about the following important factors:

The ONS’s numbers that the OBR uses in its calculations and on which its forecasts are based are unreliable. I wrote a blog piece earlier this year which focused on the ONS’s calculations of manufacturing productivity and how it had changed since the pandemic. The simple conclusion was that to believe the numbers the ONS was relying on, one had to assume that the UK manufacturing industry was run by idiots, which it very clearly isn’t. To summarise, the ONS data showed manufacturing output falling from Q4 2020 to the end of Q3 2024 by 12.2%, while manufacturing employment increasing by 1%. So, according to the ONS, UK manufacturers on average decided over this period to employ more people to produce 12% less output. In the real world, businesses just don’t do that. (Here are the charts that went with that piece.)

Given the widespread problems we already know about at the ONS and its inability to measure accurately basic metrics in the UK economy, my guess is that this glaring anomaly in its recording of what has happened to UK manufacturing industry is another error which should cast serious doubt on the reliability of any analysis of base line UK productivity, let alone how it might change over the next five years.

The next five years will see the widespread use of sophisticated AI across industry and in the public sector across the world. Industry experts have forecast that the widespread use of AI will revolutionise service industries in particular. Given that the UK is a global leader in this field, my guess is that this industrial revolution will not bypass the economy. In fact, I expect UK companies to be early adopters of the technology and reap significant productivity gains from its widespread deployment, just as other companies in other economies would.

Even if I could countenance using unreliable base line productivity data from the ONS, and even if I was sceptical about the potential productivity gains to come from the deployment of AI technology in the UK, it would still be profoundly stupid to base fiscal policy decisions today on the uneducated educated guesses of an organisation whose forecasting record was as lamentable as the OBR and especially in relation to a variable whose base line calculation should be cause for great concern.

It would be infinitely better for the Chancellor and her Treasury team to respectfully thank the OBR for their five-year forecast and state clearly that if the economy and productivity were to develop over the next five years as it forecast, fiscal policy would be adjusted contemporaneously to reflect those developments. As for the decisions to be taken now, my advice would be that tax policy should be adjusted now to reflect what is needed now, based on what is known and likely to happen over the next twelve months, something about which there has to be a greater degree of certainty.

Finally, I would draw the Chancellor’s attention to the ONS’s massive upward revision to investment spending last year. I might also ask what she thinks motivated that massive increase. My experience suggests that companies increase investment because they are looking to drive greater efficiency in their businesses, which in turn drives higher returns—in other words, greater productivity.

Budget speculation

To finish off, I should also outline what I think is going on with respect to the speculation about what the Chancellor will be forced to do in November. In summary, there are a few issues that are easily addressed.

The £30bn hole that the press now believes needs to be filled comes from, very roughly:

- £5bn of welfare spending cuts that the government failed to deliver on.

- £5bn of extra debt interest payments

- £15-£20bn from the OBR’s lower growth forecasts, which are in turn driven by the productivity changes I’ve already written about

My view is that there will probably have to be some revenue raising in the budget to cover for the failed spending cuts. That should come via a tax on betting and gaming and the freezing of personal allowances. The debt interest number is wrong, and the OBR’s March forecasts for this number should still hold good. Finally, if the Chancellor is both sensible and brave, she should take the pragmatic option and refuse to adjust fiscal policy on the back of a finger-in-the-air forecast for productivity, which she and the OBR must know is about as reliable as a chocolate teapot. What she should also be focused on is her ambition to deliver growth. She should be doing all she can to ensure that tax policy doesn’t once again crush confidence in the economy but instead liberates consumers to save less and spend more, and businesses to continue to grow investment.

In recent weeks, I’ve written repeatedly about the gap between reality and the story being told about the UK economy — and this week’s data widens that gap further. The Economist’s claim that “Britain is slowly going bust” couldn’t be more wrong. The latest ONS revisions show the economy is £60 billion larger than the OBR forecast in March, with stronger real growth, faster nominal GDP, and an extraordinary £42 billion upward revision to investment spending. That’s 1.6% of GDP — and it completely changes the picture of the UK’s so-called productivity crisis.

Far from an economy in decline, these data point to a private sector investing and expanding despite political and media pessimism. The revisions also expose the chronic weaknesses of the ONS itself, which continues to mismeasure fundamental parts of the economy — from manufacturing output to trade data — and of the OBR, whose “educated guesses” about productivity now risk dictating fiscal policy for the next five years.

As things stand, the Chancellor faces a November budget framed by an imagined “black hole” created not by reality, but by spreadsheet assumptions. Basing tax rises on these speculative forecasts would be self-inflicted economic damage. Instead, fiscal policy should focus on the near-term, not a fictional five-year horizon. The goal should be to free growth, not suppress it.

If we accept the ONS’s revised figures — and apply a little logic — it’s clear the UK’s investment story is far stronger than portrayed, and that productivity will likely accelerate as AI adoption gathers pace. Britain’s problem isn’t a lack of growth; it’s a lack of accurate measurement — and a surplus of institutional stupidity.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.