The Self-Loathing Economy

I feel I should first apologise for returning to a subject I feel very strongly about, but which should also be important to the W4 and Woodford Views audience. The subject is the outlook for the UK economy. And, by implication, the UK stock market. Both of which have the potential to continue to perform well ahead of expectations for years to come. Unfortunately, any potential ahead for a brighter future is at risk. At risk of being undermined by a self-loathing media mind virus, which manifests itself in a relentless series of lurid, but ill-informed commentary about the UK’s imagined impending economic doom.

I have been around this industry long enough to know that these challenges are an ever-present problem. However, the scale of the current media hysteria exceeds anything I have experienced in my working life. A recent story in the Daily Telegraph by Allister Heath epitomised these extremely negative views. As with all good fiction, there were strands of truth in his apocryphal story. For instance, I agree with Mr. Heath, that the UK’s economic performance has been undermined by an insane energy policy, a combination of burdensome and bad regulation, excessive levels of government spending and taxation and out of control immigration.

But, these are not new challenges, and they are not unique to the UK economy. My problem with Mr. Heath’s article (and many like it) is that there is a complete lack of balance in the narrative. None of the positives, and there are many, get a mention and, perhaps most importantly, the arguments are not supported with data. Consequently, the article feels like a one-sided rant. The author sees only a best case of gradual immiseration, or worse, a fully blown 1970s financial crisis culminating in national bankruptcy, a run on the pound, an IMF bailout, finally culminating in extreme austerity.

I think Mr. Heath is wrong and the reason for writing this blog is not only to highlight where I believe the article is fundamentally flawed but also, albeit in a very small way, to counter the overwhelmingly negative narrative we are all drowning in. A narrative which seriously runs the risk of creating its own distorted reality. To start, I thought it might help to revisit what was actually going on in the UK economy in the mid 70s when it did confront a genuine economic crisis and had to go cap in hand to the IMF in 1976.

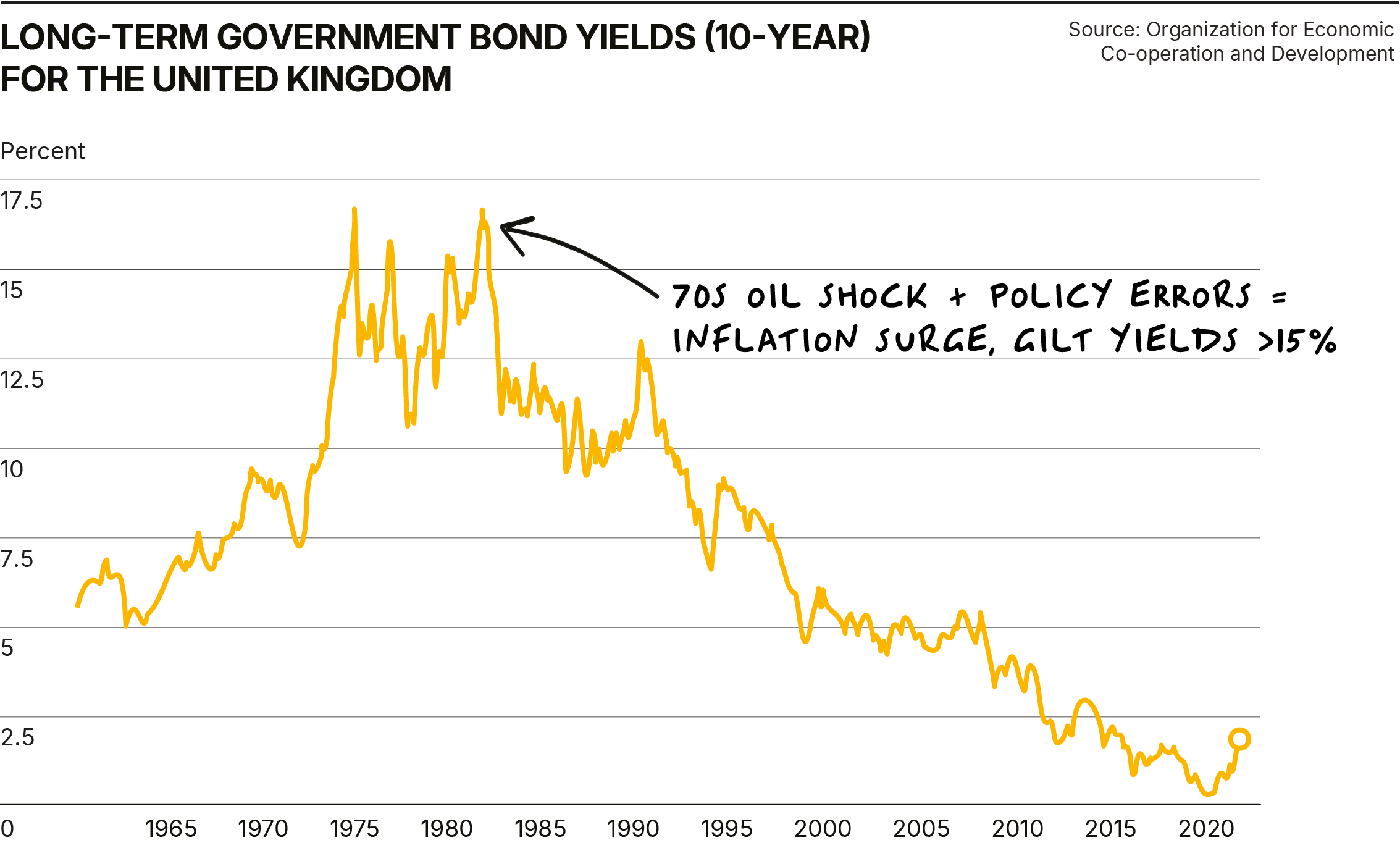

In summary, the aftermath of excessively stimulative fiscal and monetary policy in the early 70s, now known as the Barber boom was compounded by a four-fold increase in oil prices following the Yom Kippur war in 1973, a heavily unionised workforce, and a sterling crisis, which led to a barely believable rate of inflation of 25%. This economic shock combined with political and policy errors led to a mid-decade recession, bloated government spending, (the deficit peaked at 6.3% of GDP in 1976), a three-day week in 1974, base rates at 12% in October 1975, and ten-year gilt yields that exceeded 15%.

As an aside, at the start of this crisis period, manufacturing was by far the largest sector of the economy at 30.1% of total output. Services - which were at the time defined as financial services, business services, rent and real estate - were the next largest at just under 18%. So, back in the 1970s, not only was the structure of the economy totally different, but the scale of the challenges confronting the economy were of a completely different magnitude and their causes diametrically different from those confronting the UK today.

The UK’s economic challenges today are caused by excess saving in the private sector and a lack of demand caused by the legacy of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

In an attempt to differentiate myself and this blog from the depressing media rants I read so often, I thought that I should balance the established narrative not just with opinions, but also with evidence to support my more optimistic perspective. To make this a little more readable I will include charts to help illustrate the points I am going to make.

Growth

UK growth in Q2 was 0.3% which followed 0.7% in Q1. For the record, this was better than both the OBR and Bank of England had forecast. For example, in the May Monetary Policy Report the Bank said that “underlying” growth (which it didn’t define by the way) in Q1 was expected to have been around zero, indicating very weak underlying momentum in the economy. In fact, the UK looks like being the fastest growing G7 economy in the first six months of 2025. Hardly stellar growth, but neither the moribund performance described by the MPC.

Over these two quarters, the average at 0.5% is very close to the long-term average quarterly growth rate of the economy, despite the current headwinds of high inflation, high interest rates and higher taxes. My expectation for growth in 2025 is 1.5% and I expect growth to accelerate in 2026 to at least 2%. My rationale is that this will be driven principally by higher household consumption growth, reflecting in part modest real income growth and robust employment, but also less saving as households adjust to lower interest rates.

Inflation

High UK inflation, which is currently above that in Europe and the US, is in large part the product of “administered” price increases in water, electricity and gas, vehicle excise duty and minimum bus fares. In addition, last October’s budget which increased employers’ NI and the minimum wage have, amongst other things, led directly to higher food prices.

As disappointing as these inflationary pressures are, they are largely one off in nature and base effects mean that in 2026 inflation will return to its 2% target by about the middle of the year. In the stagflationary 70s, very high inflation was driven by a fourfold increase in energy prices and by excess demand in an overheating economy. In other words, nothing like the conditions that have led to this short-term inflationary spike in the UK in 2025.

This outlook for inflation combined with the ongoing moderation in wage settlements should give the MPC the scope to continue to reduce interest rates this year and in the first half of 2026 such that by the midpoint of the year rates should be below 3.5%.

Government borrowing

This government, like its predecessor, is spending too much and has had to increase taxes significantly to fund its commitments. Nevertheless, in my opinion, and based on its current spending plans going forward, it does have a credible fiscal plan that sees the overall deficit falling to 2% of GDP by the end of the forecasting period (2029/30) and, according to the OBR’s numbers, it is on track to do so. (see below)

The current budget deficit (which excludes net public investment spending) is on track to be in surplus in 2027/28. Ahead of this Autumn’s budget the Chancellor will be getting updated numbers from the OBR. It is only six months from their last forecast and, given what has happened to the UK economy in the meantime, I don’t expect there to be any justification for significant changes to their numbers.

Having said that, I suspect the OBR will slightly downgrade its GDP growth forecast (reflecting the gloomy zeitgeist) but also slightly upgrade its inflation expectation too, meaning that the deficit projections should be little changed. So, although far from an ideal fiscal situation, this planned reduction in the deficit is on track and is based on what I still believe are excessively pessimistic growth forecasts. My best guess is that higher growth in the UK over the next two to three years will deliver a better outcome than is shown here.

Households

In all the hysterical commentary about the outlook for the UK economy, barely any attention is ever paid to the biggest single determinant of economic growth. Namely; private consumption. In other words, the total value of goods and services purchased by households. In the UK it accounts for roughly 63% of GDP, whilst government spending accounts for about 44%. Put very simply, when households are confident and growing spending, tax revenues are buoyant and pressure on public finances typically eases.

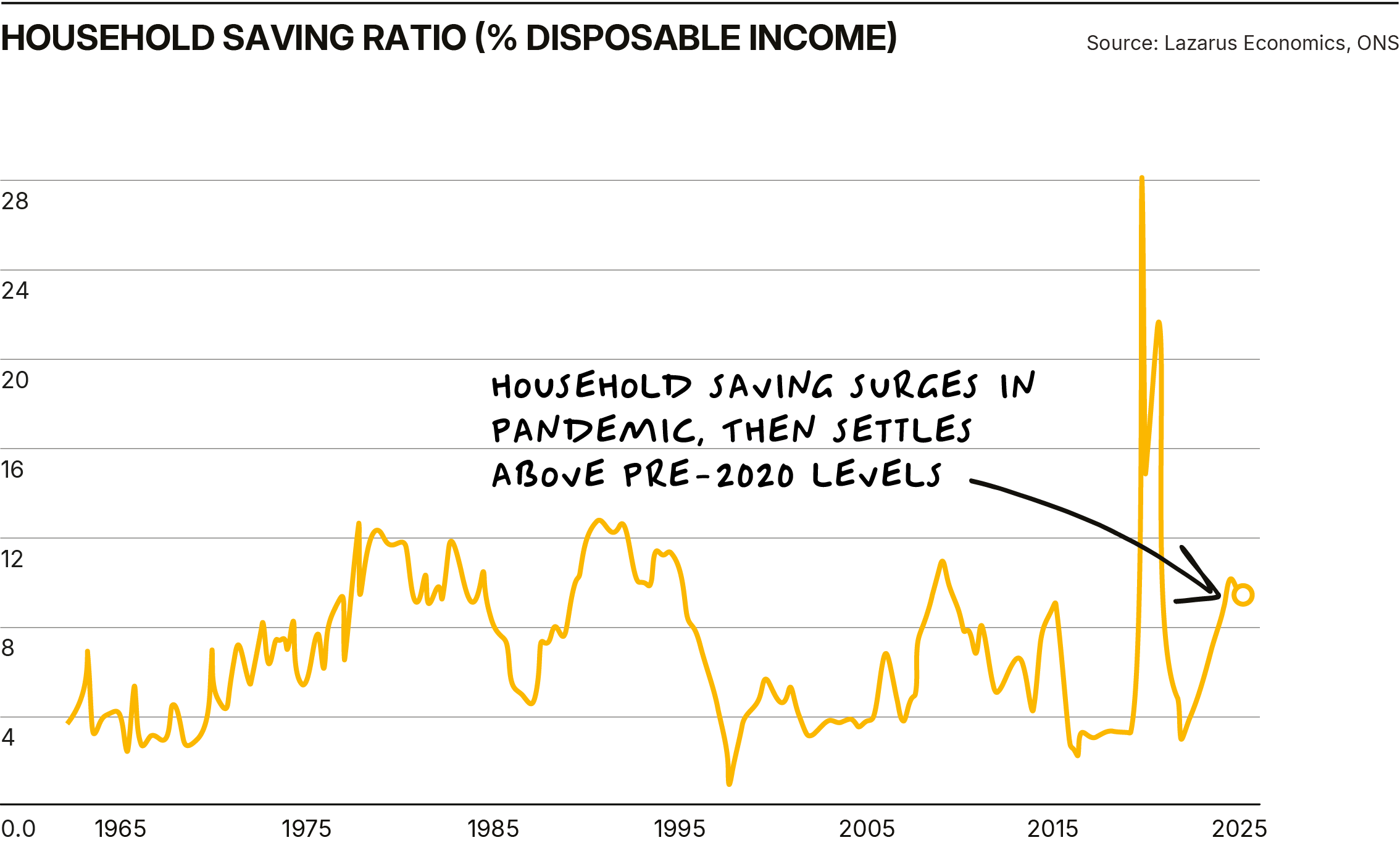

On the other hand, if consumers are uncertain and reluctant to spend, and by definition save more of their income, tax revenues are weaker and fiscal pressures can increase. Recently, and pretty much since the pandemic, UK consumers have very clearly been in the latter camp, and this is reflected in the transformation of the household balance sheet. The following charts put this recent history into perspective:

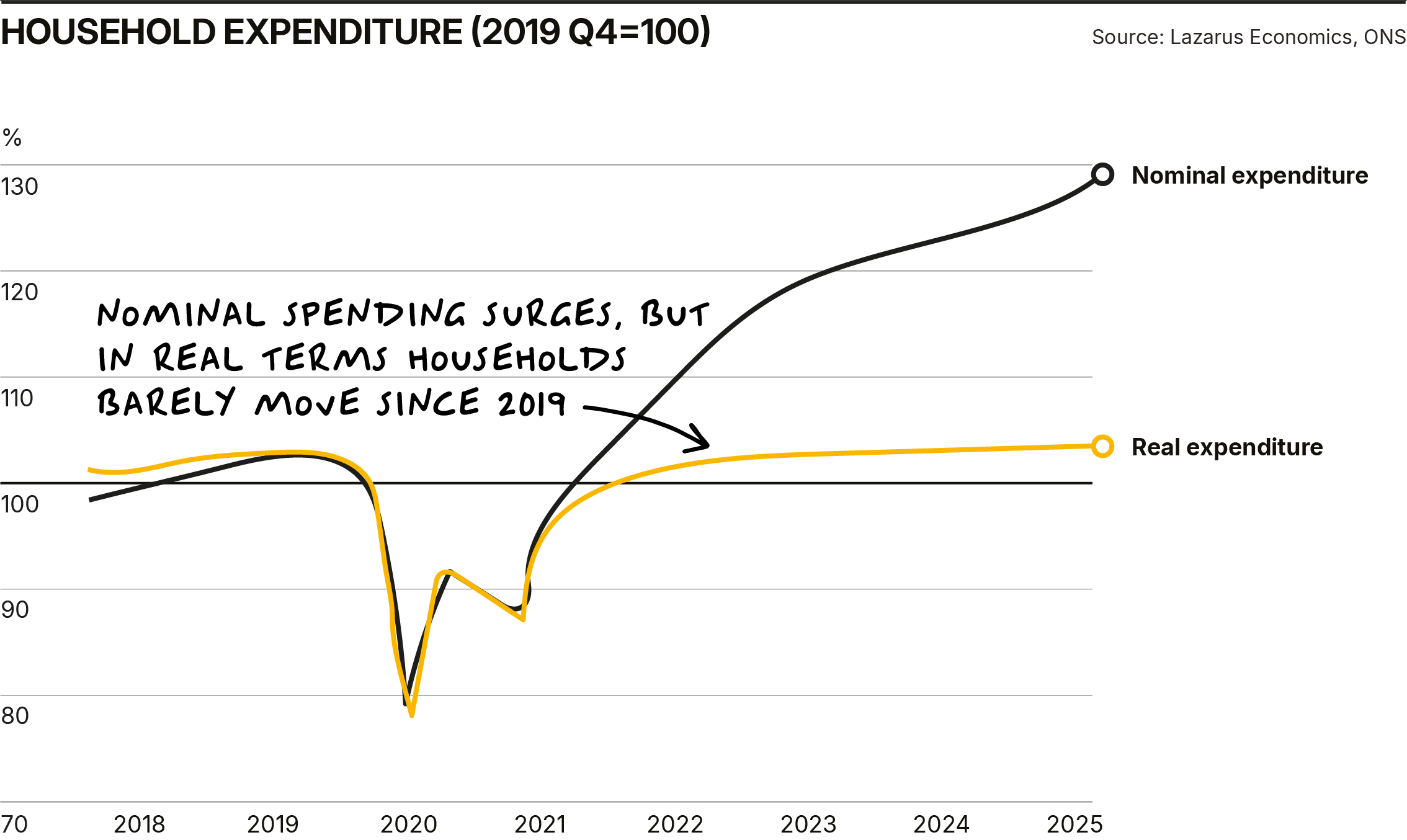

This chart shows that in real terms, household expenditure has barely grown since the pandemic. Real spending has also dramatically lagged real disposable income over the same period.

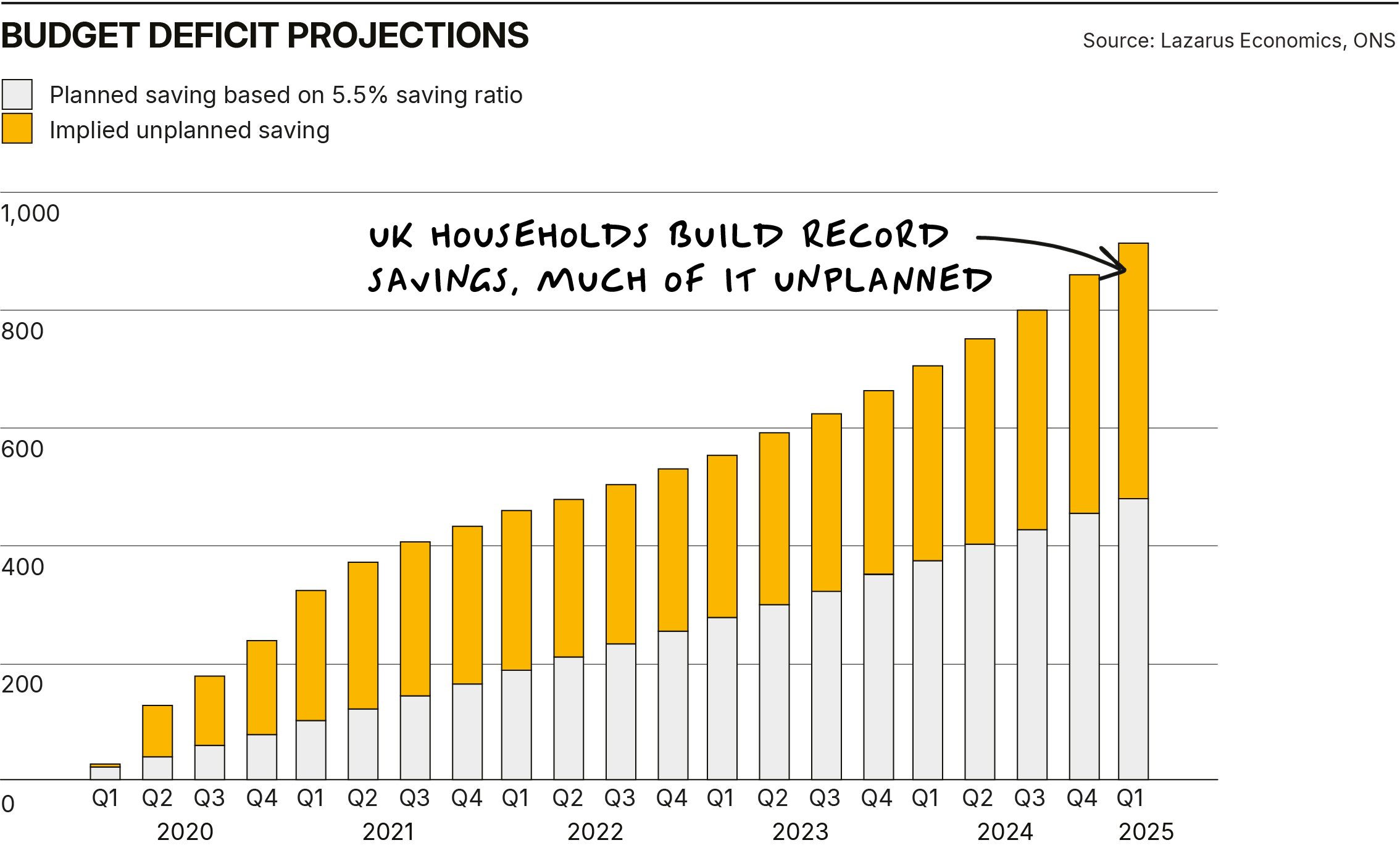

The net effect of this extraordinary and partly imposed period of thrift, is that UK households have indulged in a saving boom.

This saving boom is so significant that household bank deposits now exceed loans by a staggering £320bn. As the chart below shows clearly, immediately after the financial crisis, household loans exceeded deposits by £300bn.

This transformation in household saving and the household balance sheet is a close mirror image of the increase in the public sector’s net debt over the same period. The latter of course attracts all of the doom-laden commentary; the former is completely and utterly ignored and yet the two are inextricably linked.

In summary, since the pandemic, whilst UK consumers have held back spending and saved an unprecedented proportion of their incomes, the state has effectively become the “consumer” of last resort. It has done this by growing spending, initially funded by increased borrowing, and more recently through a blend of higher taxation and higher borrowing.

The media narrative that focuses only on the public sector and its balance sheet, and in turn claims that the economy is embarked on an unsustainable path which is doomed to collapse, are completely ignoring what’s happened to the much larger household sector. A sector which is primed to drive faster economic growth just by saving a bit less and spending a bit more.

This will happen because lower interest rates will help to improve consumer confidence and gradually erode the incentive to save and increase the incentive to spend, effectively rebalancing saving and spending behaviour. Lower rates might even catalyse an increase in borrowing, especially in the mortgage market. This isn’t just wishful thinking either; there are already tentative signs that slightly lower rates are already leading to a recovery in borrowing from very depressed levels, in the mortgage market:

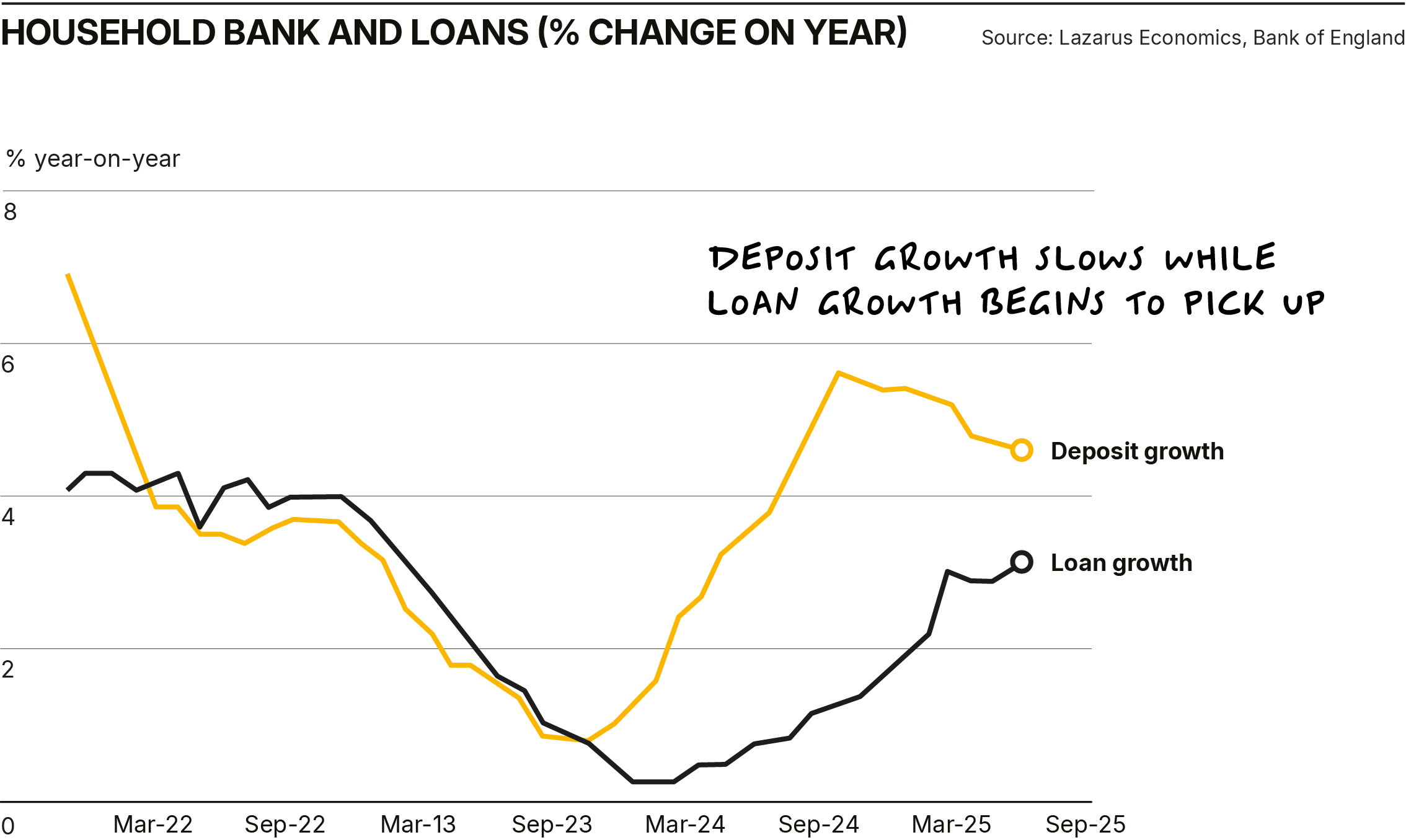

And having the predicted impact on deposit growth, which is slowing, and loan growth which is also picking up.

The latest bank lending data for the three months to the end of July show this pick up in mortgage lending but also show consumer credit up 7% YOY and corporate lending up 8.9% YOY.

Conclusion

So, I see things quite differently from the prophets of doom, such as the NIESR, Mr. Heath from the Daily Telegraph, and the rest of the financial media pack. Instead, what I see in the medium term, is an economy achieving growth of 2% or more, driven by a relatively modest rebalancing of saving and consumption behaviour in the household sector, catalysed by lower interest rates, in turn driving higher tax receipts and a better fiscal outcome than the OBR currently anticipates.

This may not be economic nirvana; in many respects it is far from it. But it is so much better than the extreme pessimism that so preoccupies the consensus. Indeed, even before the impact of lower rates on the household sector’s saving behaviour is evident, we are already seeing the economy deliver growth ahead of its peers. Who knows, I could even be too pessimistic!

P.S. Having outlined why I think the economy can outperform gloomy expectations in the short to medium term, I should also emphasise that there are some longer term challenges the economy confronts which must be addressed if the economy is to thrive and prosper beyond the immediate future. I have written about some of these issues in the past and will do so again in the next blog piece that will outline the nature of the most pressing, and the radical public policy decisions our political leaders must take to solve them.

The UK economy is not heading for the catastrophe that so many commentators would have you believe. Yes, challenges exist — inflation, energy policy, high government spending and taxation — but these are not new, nor unique to the UK, and certainly not comparable to the 1970s crisis, when inflation hit 25%, sterling collapsed, and the IMF was called in. Today’s situation is entirely different: growth in the first half of 2025 has already outpaced forecasts, making the UK one of the fastest growing G7 economies. Inflation, largely the product of one-off administered price rises, is set to fall back to target by mid-2026, giving the MPC room to lower rates below 3.5% over the next 18 months.

The government’s finances are not perfect — spending remains too high — but the deficit is on track to fall to 2% of GDP by the end of the decade, and even reach current budget surplus by 2027/28. In fact, I expect stronger-than-forecast growth to deliver a better fiscal outcome than the OBR projects. The media’s relentless focus on public debt also ignores a much bigger story: the transformation of household balance sheets. Since the pandemic, households have built up unprecedented savings, swinging from a £300bn deficit of loans over deposits to a £320bn surplus today. This private sector thrift is the mirror image of public debt growth, yet it receives no attention.

As rates fall, the incentive to hoard cash will diminish. We are already seeing tentative signs of change: mortgage lending is rising, consumer credit up 7% year-on-year, and corporate borrowing nearly 9%. With household consumption making up 63% of GDP, even a modest shift from saving back to spending will be a powerful driver of growth, tax receipts, and improved fiscal health.

Far from sliding into decline, the UK economy is well-positioned for 2%+ growth over the next few years — a path that is far more realistic than the apocalyptic scenarios dominating the headlines.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.