Punch and Judy Show

Once again, I have been stung into action by the relentless drivel emanating from the financial media and politicians. This prolonged pre-budget period has provided fertile ground for those with an opinion to voice it loudly and repeatedly. Unfortunately, the facts, once again, appear not to be relevant to this discourse and certainly play no part in the weekly Punch and Judy show at PMQs in the House of Commons. In general, the government comes under pressure for its tax-and-spend policies, whilst Kier Starmer accuses the opposition of causing the productivity problems that increasingly appear to be at the centre of the debate about what the OBR will say in a few weeks, and how the Chancellor will respond to those forecasts.

To describe this situation as ridiculous is to flatter it. The economy waits with bated breath whilst the ONS, OBR, Treasury, Chancellor mumble**** decides what will happen to the taxes we will pay, apparently based on their collective finger-in-the-air judgement of UK productivity over the next five years.

Bear in mind that productivity is something the ONS has been incapable of measuring accurately in the past, and which, ironically, was upgraded significantly following the upward revisions to GDP a few weeks ago. Remember as well that the ONS has itself cast considerable doubt on the accuracy of its employment data (the Labour Force Survey), which it in effect believes is overstating the number of people in work (this is the denominator in the productivity calculation). Finally, also remember that the OBR has itself described productivity forecasts as uneducated educated guesses (to paraphrase).

It beggars belief that the Chancellor will apparently have to base her tax decisions on what are effectively guesses for both baseline and downgraded forecast productivity, just after it’s just been upgraded following recent upward revisions to nominal GDP, and ahead of what is widely accepted as a productivity industrial revolution as AI is rolled out across every corner of the economy. The application of a modicum of common sense might dictate that five-year forecasts of future productivity should be increased, not downgraded right now, to reflect the impact of that industrial revolution, but unfortunately, that sort of pragmatism appears to be in very short supply in the corridors of power.

One might have thought, given the inherent flakiness of productivity measurement, that instead of treating it as an input, the collective wit of the OBR would be focused on trying to assess what growth the UK economy might deliver over the medium term based on a more straightforward judgements of, for example, what households will be spending in the future. That, of course, will be a function of their collective decisions based on incomes (more easily forecastable), savings (a known) and borrowings (a known) and how these evolve over time in response to lower interest rates. (see below) Through a process like this that also looks at government spending (pretty predictable) and investment spending (which is growing and starts from a £42bn higher base following recent ONS revisions), it should be possible to get a pretty well-informed view on what will happen to growth (output) over the next few years. Based on trends in employment and hours worked (NOT the Labour Force Survey, or LFS), it should then be possible to calculate changes in productivity as an output. That’s what I would do. It’s a lot more straightforward and, in my view, a more reliable way to anticipate the future. Unfortunately, I suspect the OBR will default to its more arcane approach, which has historically been long on complexity and, frankly, poor on accuracy in relation to outcomes.

Quite why the inherent volatility and historical unreliability of productivity data have not led to a more circumspect attitude toward its use as a predictive tool is bewildering. Just by way of example, take recent history. Productivity fell in the UK in 2023 and 2024, according to the ONS, yet economic growth was positive in both years and indeed accelerated during this period as the economy recovered from the energy price, inflation, and interest rate shock that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In 2024, according to the ONS, output grew by 1.1%, but total hours worked increased by 2%. Anyone who’s worked in a business knows that this isn’t how they work. Successful businesses – namely the ones that survive – don’t use more labour to get less output. (I wrote a blog on this subject earlier in the year that focused on UK manufacturing, which highlights the implausibility of the ONS’s productivity data in this highly competitive industrial sector.)

For anyone that doubts my perspective or believes that this data must be accurate, I would challenge them to have a go at calculating the output of the business that employs them – that is the total amount of the goods and services their business produces over a given period. And just by way of an example, I would welcome suggestions on how to calculate the output of a school during a holiday, or even during term time, or a fire station that has never extinguished a fire, or for that matter, the entirety of Whitehall? What might be the output of the armed forces or of a law firm or an insurance company? By the way, revenue is a poor proxy for output because a business or indeed a government department or the NHS can increase its revenue through actions that do not reflect an increase in its core production of goods and services simply by raising prices. It’s when you start to encounter this level of complexity and guesswork that you can imagine the challenges the ONS confronts calculating output for the entire economy based on survey data where response rates have been falling consistently in recent years.

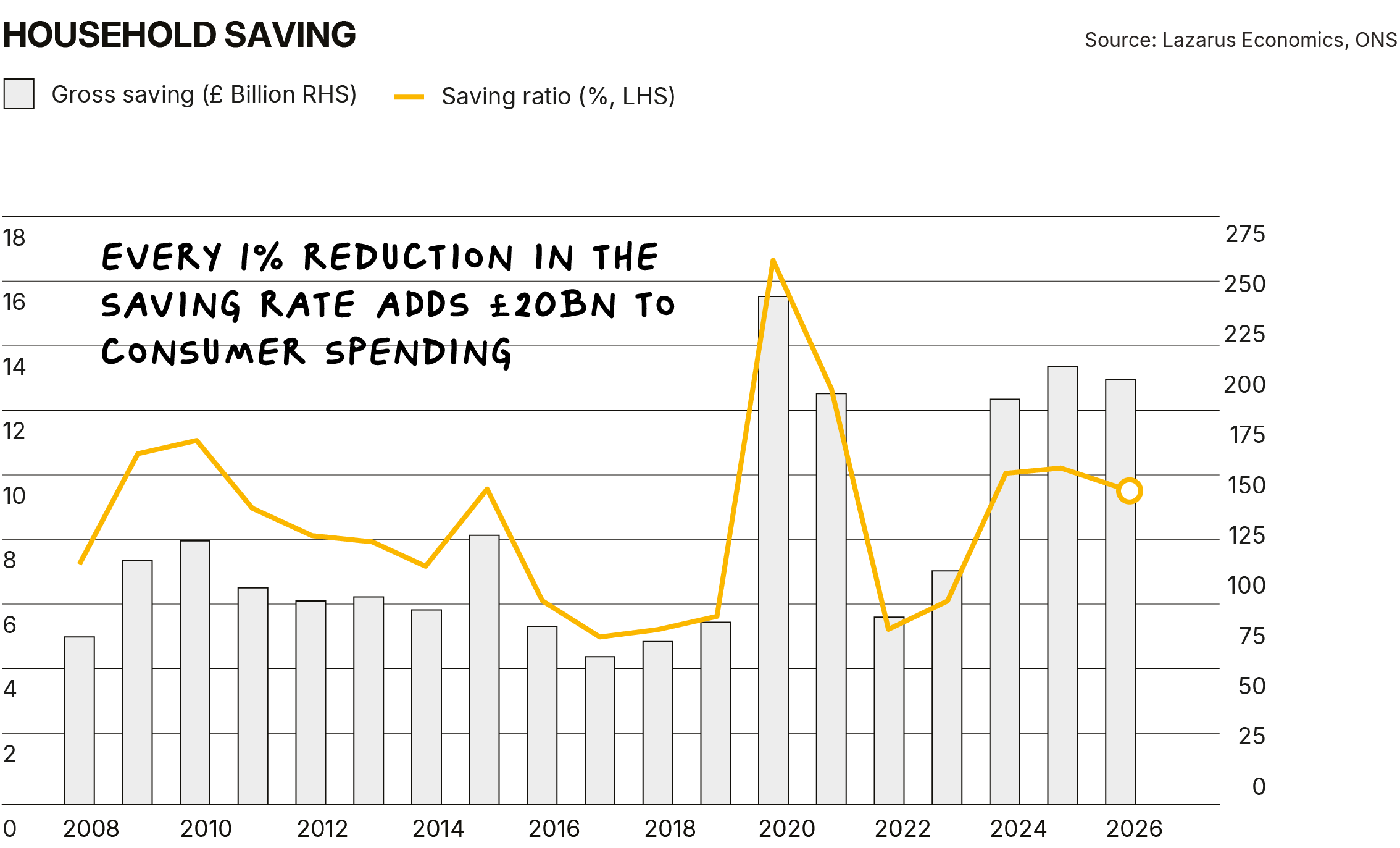

Quite what will happen next week is not yet clear and is unlikely to be so until the Chancellor has sat down on the 26th November after giving her budget speech. I still believe that she should resist the pressure to succumb to speculation masquerading as fact in the OBR forecasts for the UK economy over the next five years. As for what this means for mythical fiscal black holes and what will be done to fill them, my guess remains that there will be tax increases but nowhere near the scale of those envisaged by the media. And finally, for those worried about how tax increases might impact the economy, bear in mind that every 1% reduction in the saving rate from its currently very elevated level of just over 10%, would add about £20bn to consumer spending.

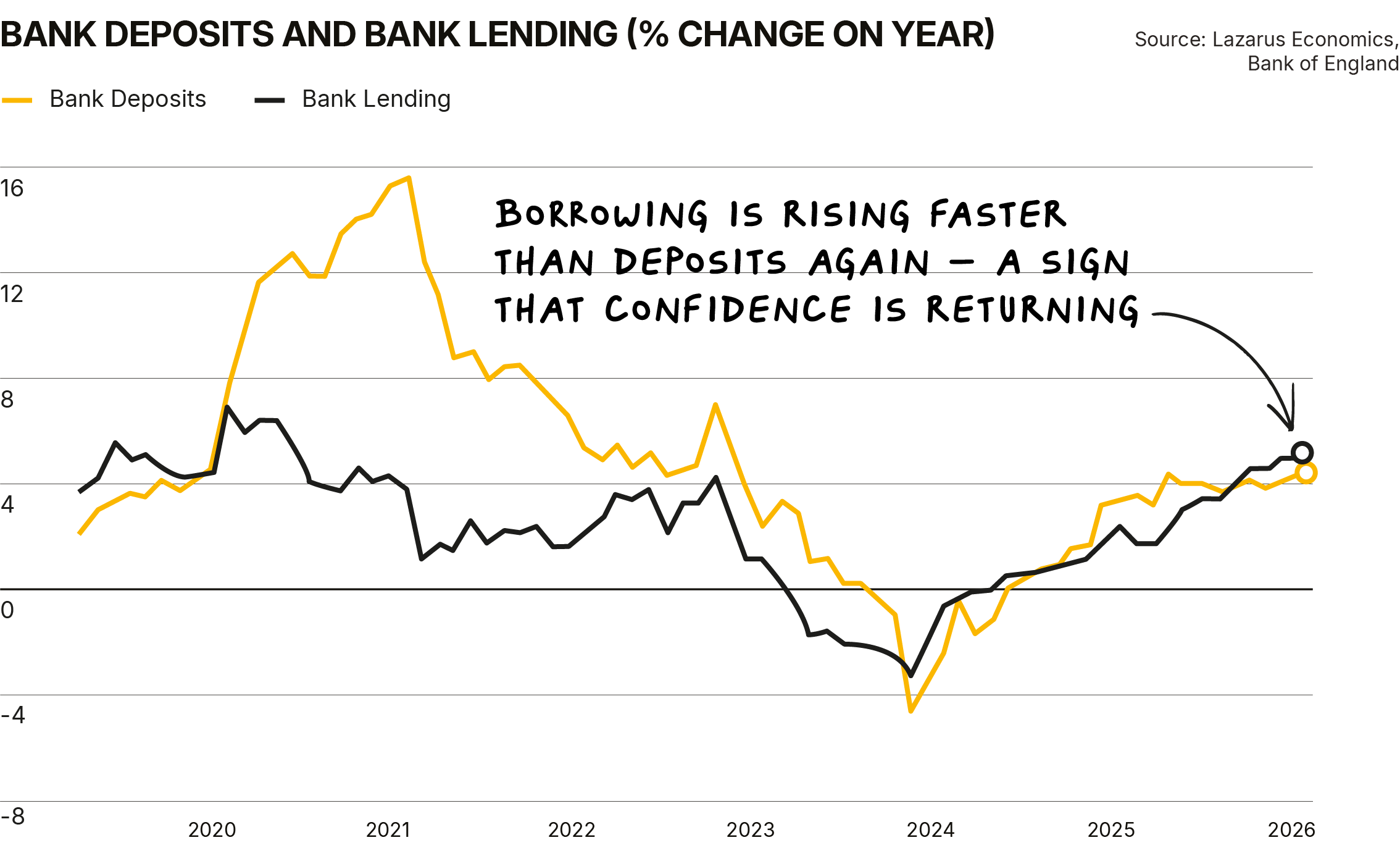

Having dwelt on this rather technical and possibly boring subject, (about which you may have gathered I am somewhat exercised) I thought I should finish on a more positive note. In recent months there has been increasing evidence of better momentum in the economy which has seemingly gone unnoticed in the media and received virtually no attention from economic commentators. Possibly this is because the indicators of this improving economy are somewhat old-fashioned monetary indicators which neo-Keynesian economists (like those at the Bank of England) tend to ignore or dismiss.

Here is a series of easily understood charts that I think paint a clear picture of the economy's momentum.

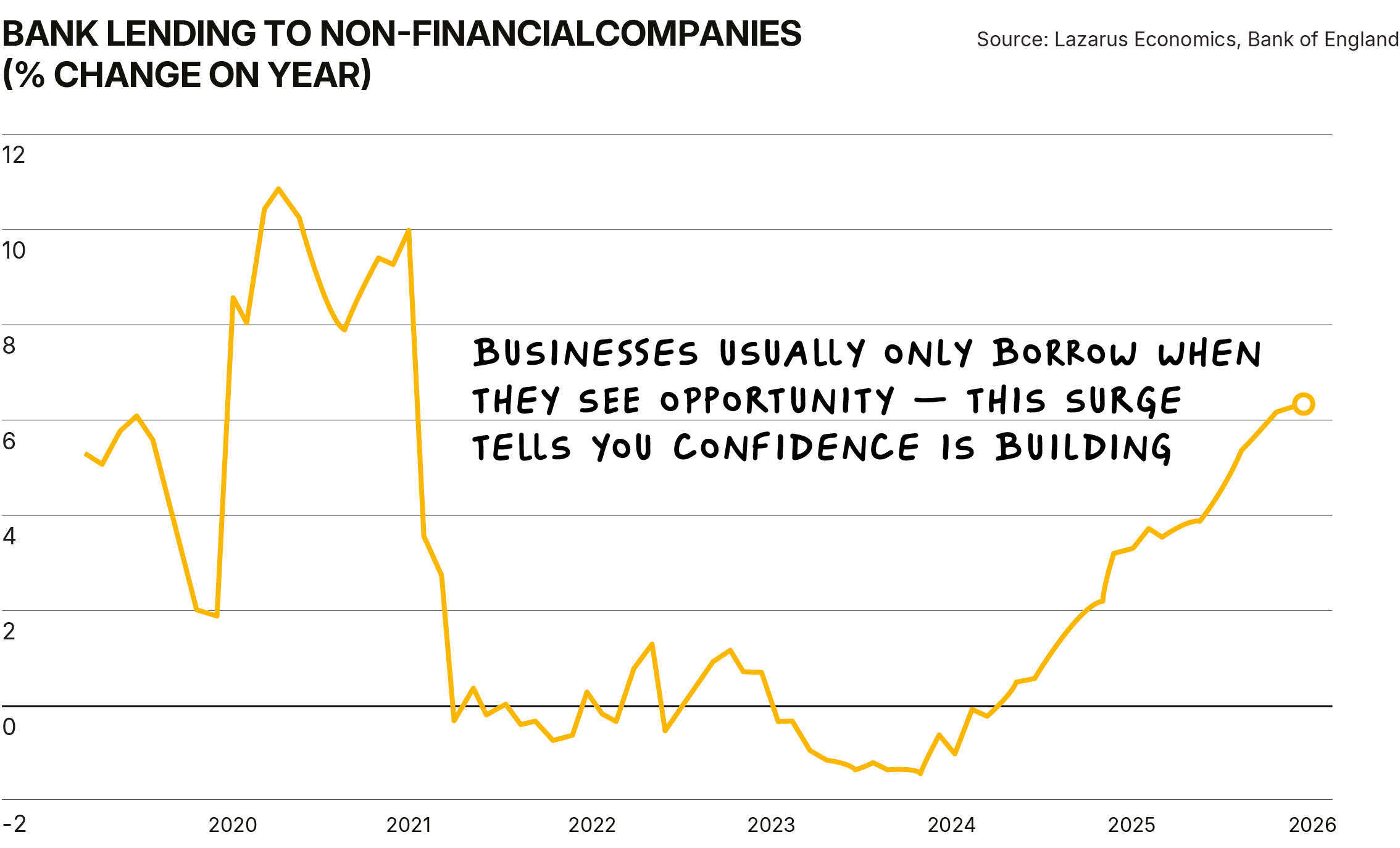

The first looks at loan growth, which, after being negative in 2022 and 2023, is now growing quite strongly in the context of the last five years and is now outstripping deposit growth.

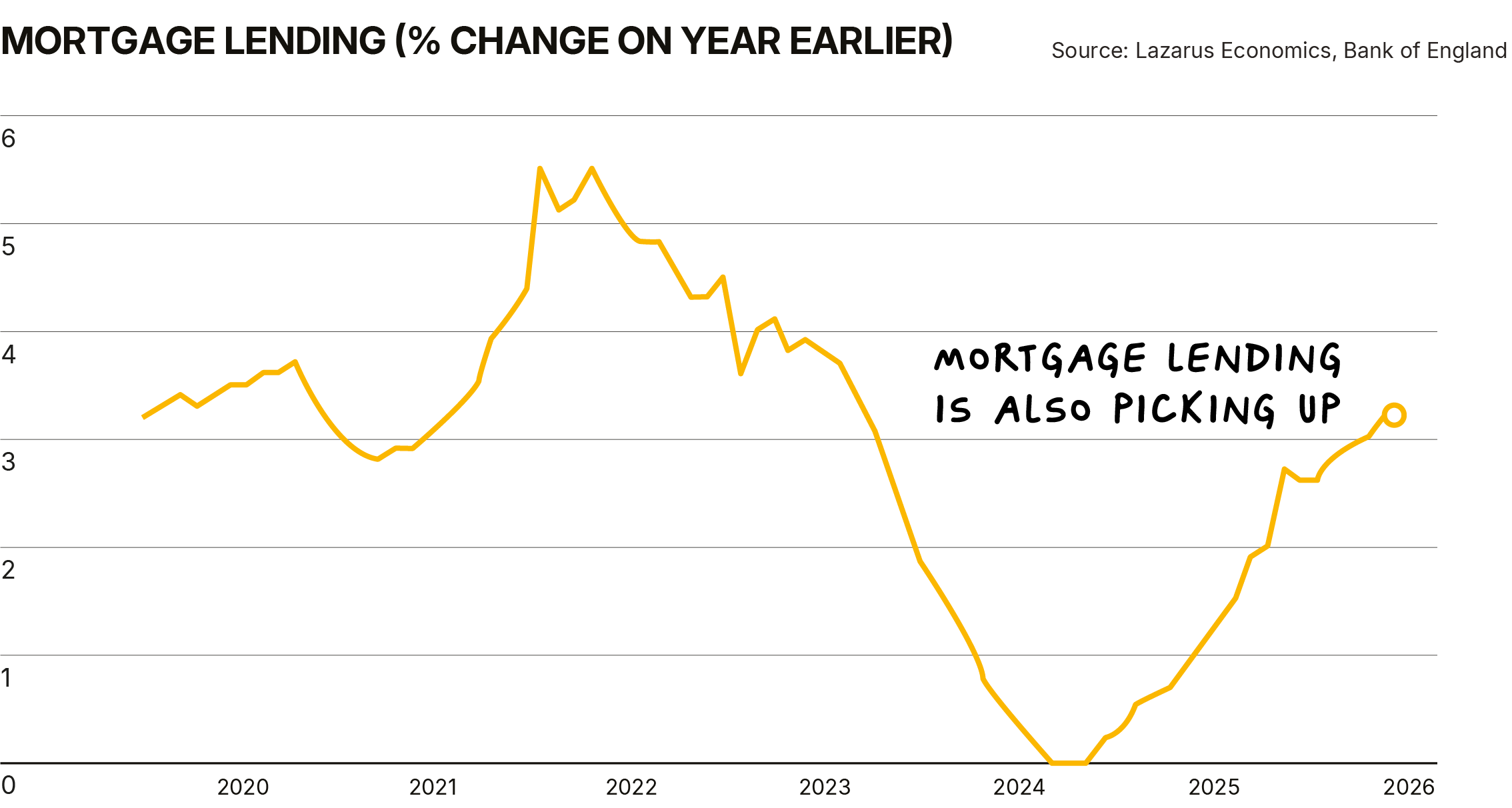

This is reflected in a pickup in mortgage lending and, more recently, stronger growth in consumer credit, which is now growing at over 7%.

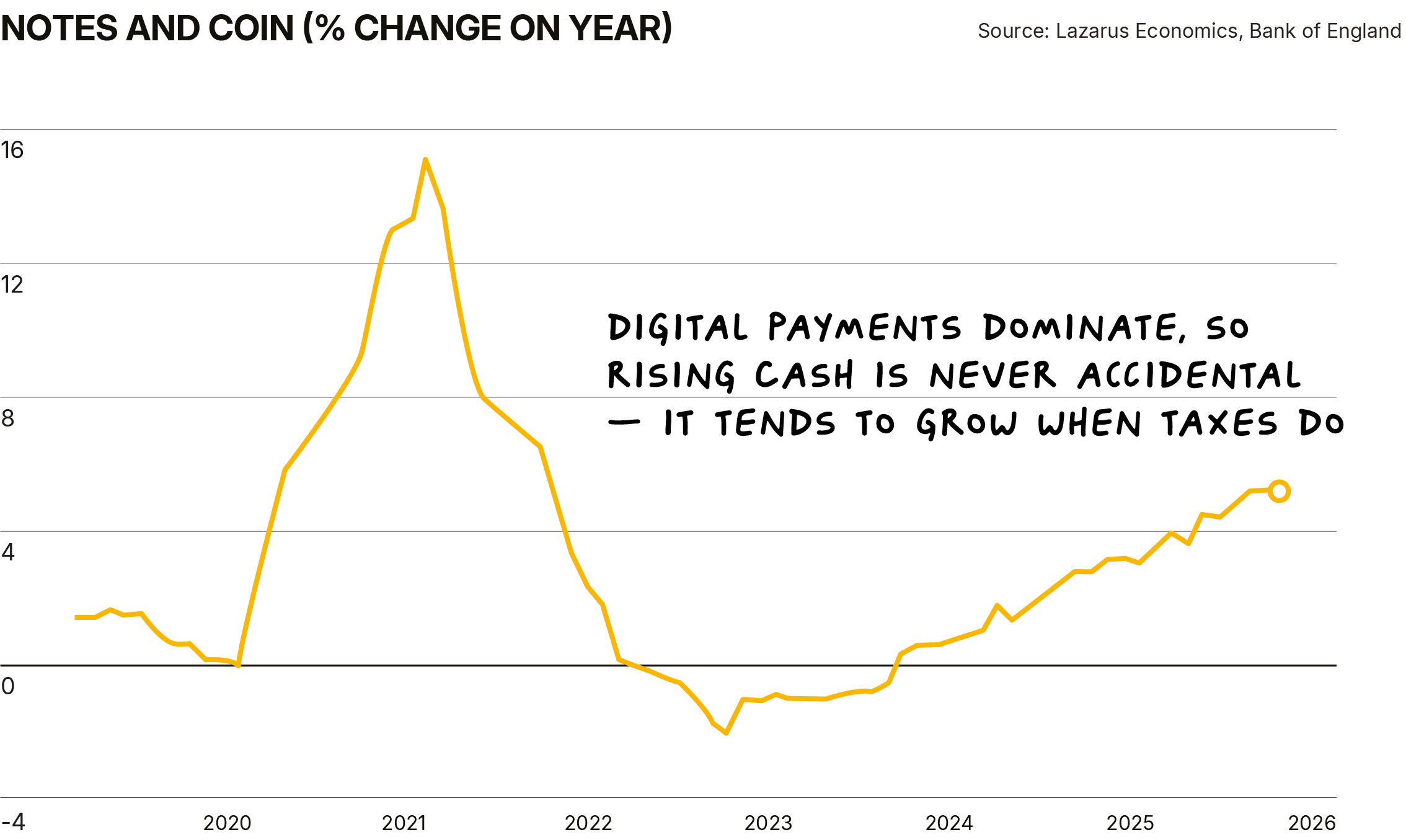

Also of interest is the noticeable growth in notes and coin (narrow money) which may reflect a growing black economy as people seek to avoid high taxation.

Perhaps most dramatic of all is the very dramatic change in bank lending to non-financial companies. It may be obvious, but it’s worth noting that businesses don’t increase borrowing when they lack confidence in the economy's outlook.

What’s clear to me is that something is stirring in the UK economy right now, and I expect this momentum to build in the months ahead. We will get a cut in interest rates next month and more next year. These cuts will be pivotal in driving greater confidence in the economy, stronger loan growth, more spending, less saving, and ultimately higher growth.

Frankly, my 2% growth expectation for next year is beginning to feel too low. Anyone want a wager?

I’ve written this because the pre-budget noise about “weak productivity” and “fiscal black holes” has become detached from reality. Politicians and the financial media are treating the OBR’s productivity assumptions as hard fact, even though the underlying data and methodology are, at best, highly questionable.

The ONS itself admits it struggles to measure output and has cast serious doubt on its own Labour Force Survey, which feeds into productivity calculations. The OBR, meanwhile, has described productivity forecasts as educated guesses. Yet on this shaky foundation, the Chancellor is expected to decide how much extra tax we all pay over the next five years. That is absurd – especially when we’re on the cusp of an AI-driven productivity shift that common sense suggests should push forecasts up, not down.

If I were doing this properly, I wouldn’t start with productivity at all. I’d start with growth: what households are likely to spend, given incomes, savings, and borrowing as rates fall; what the government plans to spend (largely known); and how investment evolves from a higher base after recent revisions. From that, you can build a view of output and then derive productivity as an output, not treat it as a mysterious input that dictates everything else.

Recent history already shows how flaky the official story is. According to the ONS, productivity fell in 2023 and 2024 even though the economy grew, and growth picked up as we recovered from the energy and interest-rate shock of 2022. The data imply we used more labour to get proportionately less output. Anyone who has ever run a business knows that is not how successful firms behave over time. The deeper you think about how you’d measure the “output” of schools, fire stations that never fight fires, large parts of Whitehall, law firms or insurers, the more obvious it becomes how much guesswork is involved.

Despite this, we are told: productivity is weak, therefore growth will be low, therefore taxes must soar. I don’t accept that. I still expect tax rises, but nowhere near the scale some commentators are bandying about. And even then, remember the savings rate is still over 10% – every 1% fall releases roughly £20bn of extra consumer spending. That’s a powerful buffer.

More importantly, the underlying monetary signals are turning distinctly positive and barely anyone is talking about them. Loan growth, which was negative in 2022–23, is now firmly positive and running ahead of deposit growth. Mortgage lending has picked up, and consumer credit is growing strongly. Notes and coin in circulation are rising, which may also hint at a growing black economy as people try to avoid high taxes.

Most striking is the sharp rise in bank lending to non-financial companies. Businesses don’t borrow more when they’re gloomy; they do it when they’re preparing to invest and expand. Something is clearly stirring in the UK economy. With likely interest-rate cuts ahead – possibly starting as soon as next week and more to follow – I expect confidence, loan growth, spending and activity to build from here.

Put simply: the official narrative is fixated on fragile productivity guesses and mythical fiscal holes. The real world is telling a different story – one of gathering momentum. My 2% growth forecast for next year is starting to look on the cautious side.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.