Pre-Budget Politics: Lies, Lunacy and a £20bn Mistake

Maybe I am obsessing about this upcoming event too much, but having listened to the Chancellor’s woolly, boring pre-budget speech, I felt compelled, again, to put pen to paper. We also covered it extensively in the W4.0 Podcast “Noise Cancelling”.

This was an unusual event. Indeed, I can’t remember another occasion when a sitting Chancellor felt compelled to soften up her audience ahead of the actual budget with this sort of scene-setting speech. Perhaps not surprisingly, it was much more about politics than economics. In the process of managing the expectations of business, consumers and her own backbenchers, she outlined the challenges she confronts, the apparently dreadful legacy she inherited and reiterated her approach to fiscal discipline.

My conclusion is that this was an exercise in expectations management in which she was laying the ground for tax increases alongside some degree of spending discipline. It’s also becoming increasingly clear that the OBR’s finger-in-the-air productivity forecasts, which will be downgraded, will affect its growth assumptions and, by definition, the future fiscal arithmetic. What is still not clear, and won’t be until the speech is delivered, is how the Chancellor will respond to these new forecasts and what she will do to address the implications of what the OBR concludes.

Having said that, there were a couple of things in this speech which I wanted to comment on and to illuminate with some data.

In seeking to justify the extra taxes and spending restraint hinted at in the speech, the Chancellor sought to lay the blame on a number of popular culprits. Namely:

- Previous Tory economic mismanagement – Brexit, etc

- Liz Truss’s 2022 mini-budget

- Excessive government debt and high interest costs

- High and persistent inflation

- Increased economic uncertainties, including tariffs

- Historic underinvestment

- Low productivity/low growth

As Sara Paretsky once said (to paraphrase), dull lies were effective because they would be so boring that no one would question them. Well, on this occasion, despite what was a pretty dull and repetitive speech, I will challenge the half-truths it contained.

Tory economic mismanagement

It’s hard to argue that previous Tory administrations did a good job. On so many issues, their judgements were just wrong, from George Osborne on. Having said that, though, there is absolutely no evidence to support the claim that Brexit damaged the economy. On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence of the damage done by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. My problem with Rachel Reeves blaming the economic and debt legacy of these events on previous Tory administrations is that if the government at the time had followed the advice of the then opposition, the damage inflicted on the economy would have been considerably worse (longer lockdowns, more support during the cost-of-living crisis).

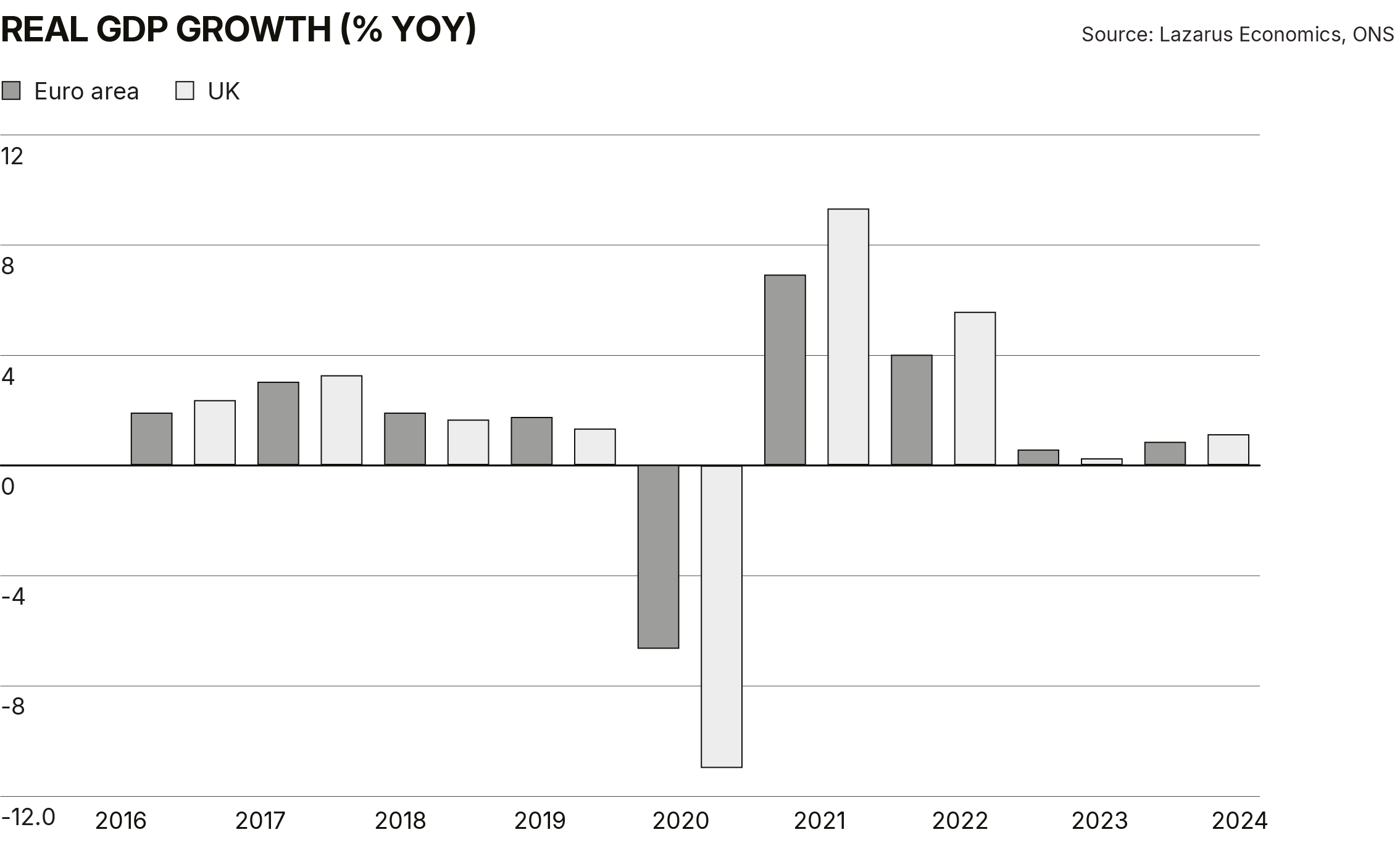

In her speech, Rachel Reeves cited the damage done by Brexit, along with other Tory mismanagement, for the UK’s disappointing economic performance. Whilst the UK has indeed materially underperformed the US economy, no such evidence of underperformance against our EU peers exists. Yet this lie is repeated so often that it has become accepted as “truth”.

The average growth rate of the Euro area and the UK since 2016 is identical at 1.5%. The average since 2020 is 1% for both as well.

Liz Truss’s mini-budget

Bizarrely, Liz Truss’s mini-budget, which was never enacted, and her 49-day administration got a mention in the Chancellor’s speech. Quite how anyone would believe that Liz Truss might bear responsibility for this government’s woes (she resigned just over three years ago, having been in office for just over a month) is beyond me. I have to say this really was the definition of grasping at straws.

Excessive government debt and high interest costs

I agree with Ms Reeves that debt is too high here in the UK. The problem, however, and something she and the Labour government are incapable of admitting, is that government spending is too high. It seems somewhat ironic that one of the rumours doing the rounds at the moment is that the Chancellor might be envisaging raising the basic rate of income tax for the first time in 50 years (I doubt it, by the way). The last time this happened (in 1975), Dennis Healey was the Chancellor. He was presiding over an economy in which taxes were 40% of GDP (pretty much where they are now) and spending was about 46% of GDP (pretty much where it is now). One might have thought that the lessons learned over the preceding fifty years might have had some impact on this government’s thinking about spending and tax, but it appears not. Its answer to this problem is not that spending is too high but that taxes are too low. Madness.

As for high interest costs, these are in large part the product of high UK base rates, which, at 4%, are high because inflation is similarly high. Again, rather ironically, just over a year ago inflation was at 2% but has risen to today’s 3.8% in large part due to the measures this Chancellor introduced in last October’s tax-raising budget, including on public sector pay—the definition of a self-inflicted wound.

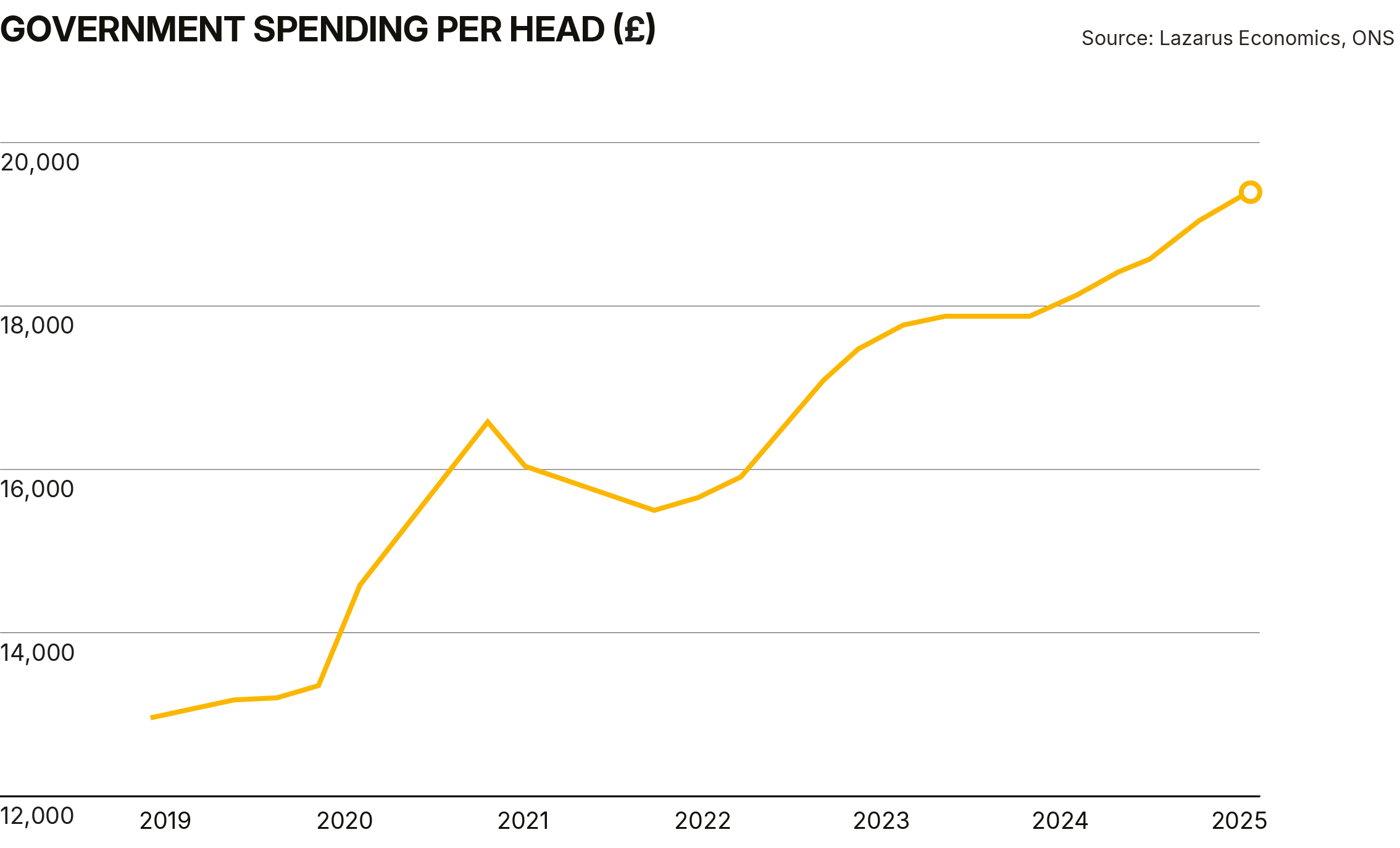

To help reinforce these points, here is some data.

- Total government spending was £1.34trn in the four quarters to Q3 2025. That’s around £19,000 per head of population.

- That’s about £6,000 per head more than just before the pandemic. (In real terms, that’s £2,000 more.) Only £1,000 of the £6,000 is due to higher debt interest. The rest is higher welfare spending, higher public sector pay, etc.

- Government debt is about £40,000 per head, by the way.

High and persistent inflation

Last September, before Rachel Reeves’ first damaging, tax-raising budget, inflation was at 2%, bang on target. The high and persistent inflation the economy has endured for much of 2025, to which she referred in her speech, is in large part attributable to the measures she introduced in that budget, which led directly to higher whole-economy inflation, especially higher food prices. This was all very predictable, and I indeed highlighted the budget’s damaging inflationary implications in a blog I wrote at the time.

Increased economic uncertainty and tariffs

I am afraid this is nonsense once again. Let’s start with tariffs. UK goods exports to the US over the four quarters to Q2 2025 were £64.1bn. They fell by 5.9% according to the ONS on the corresponding period to Q2 2024. That’s a fall of £4bn, which is 0.14% of GDP. Is the Chancellor really suggesting that one of the new significant challenges this government confronts that had not been anticipated in March this year (the last time the OBR/Treasury/Chancellor put their respective heads together to think about the economy) is something that amounts to 0.14% of GDP? Don’t forget that services exports have continued to grow strongly over this same period. This is just not credible.

What is even less credible was the Chancellor’s claim that heightened economic uncertainty was another thing which hadn’t been anticipated back in March. This was, by implication, cited as another reason for the heavily hinted need to raise taxes. The reality is that, back in March, the OBR was forecasting 1% growth in 2025. Since then, the data has been better than expected, and now the growth outcome for 2025 looks to be 1.5%. So, heightened economic uncertainty has coincided with an upside surprise in UK growth (at least to the OBR but not, as you might know, to me). I might even suggest that this is embarrassing for the Chancellor.

Historic underinvestment

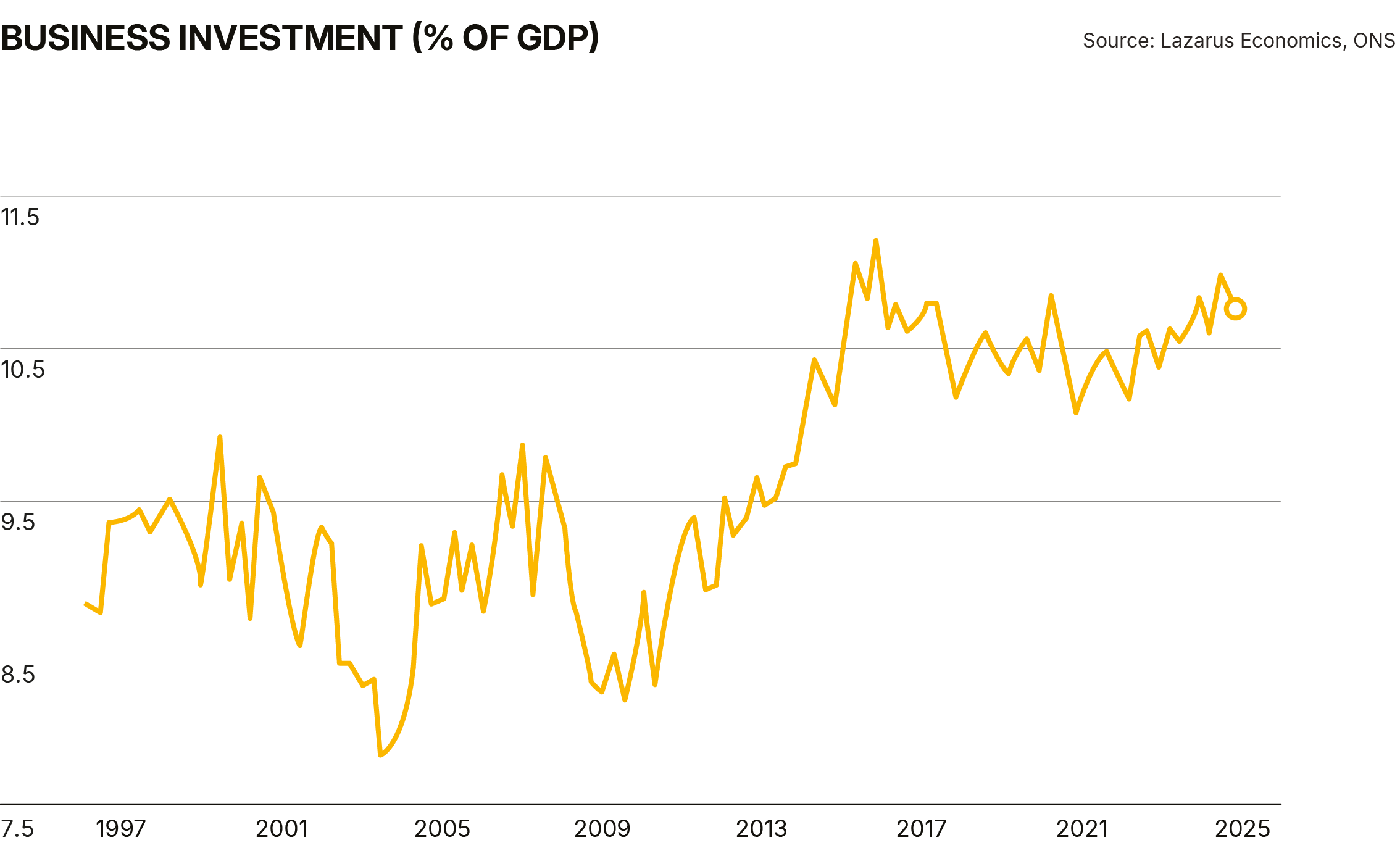

This is yet another lie told so often that it has become an accepted truth. The fact is that, as a % of GDP, business investment in the UK is close to a 30-year high and, when adjusted for the proportion of the economy accounted for by the capital-intensive manufacturing sector, looks high compared with G7 peers.

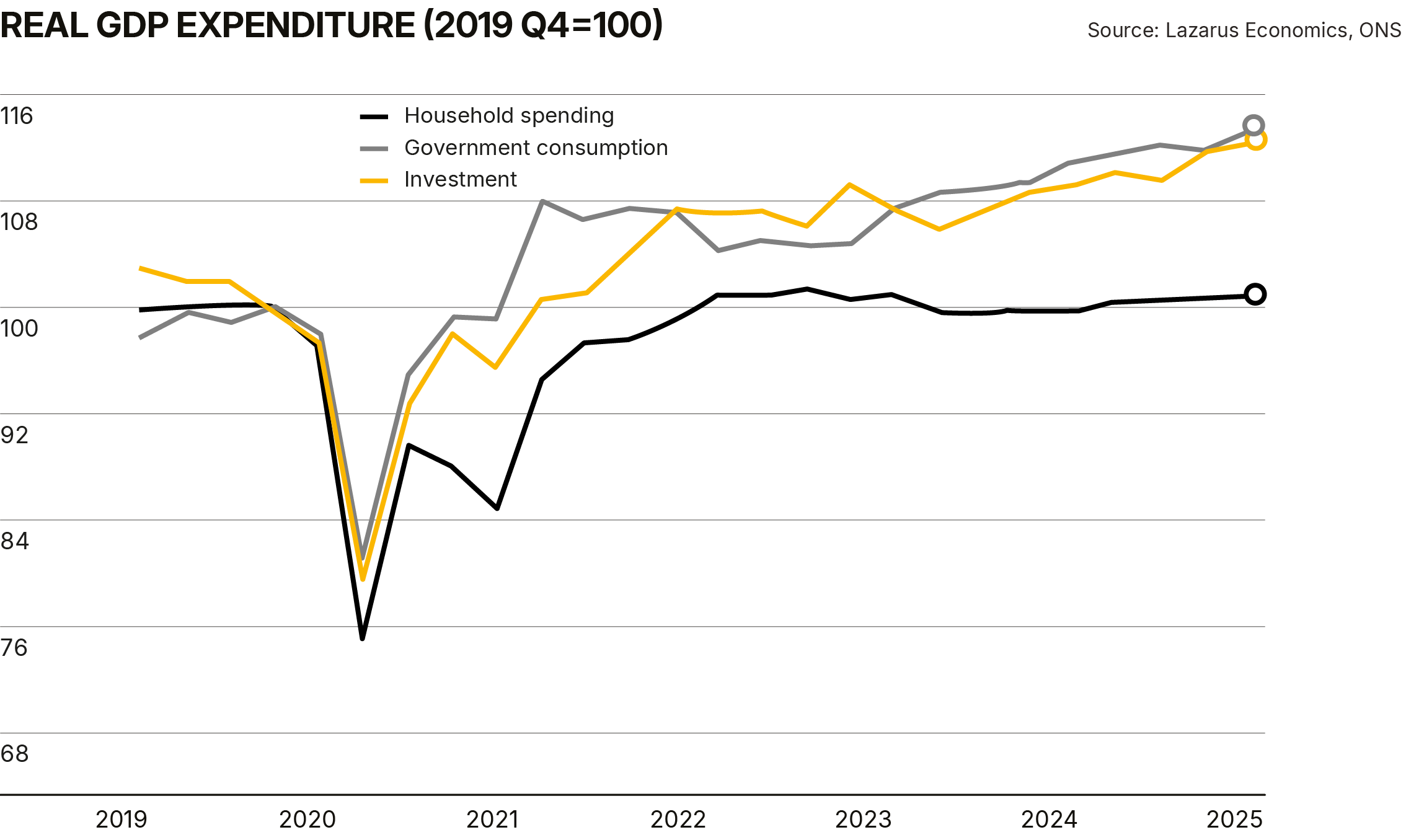

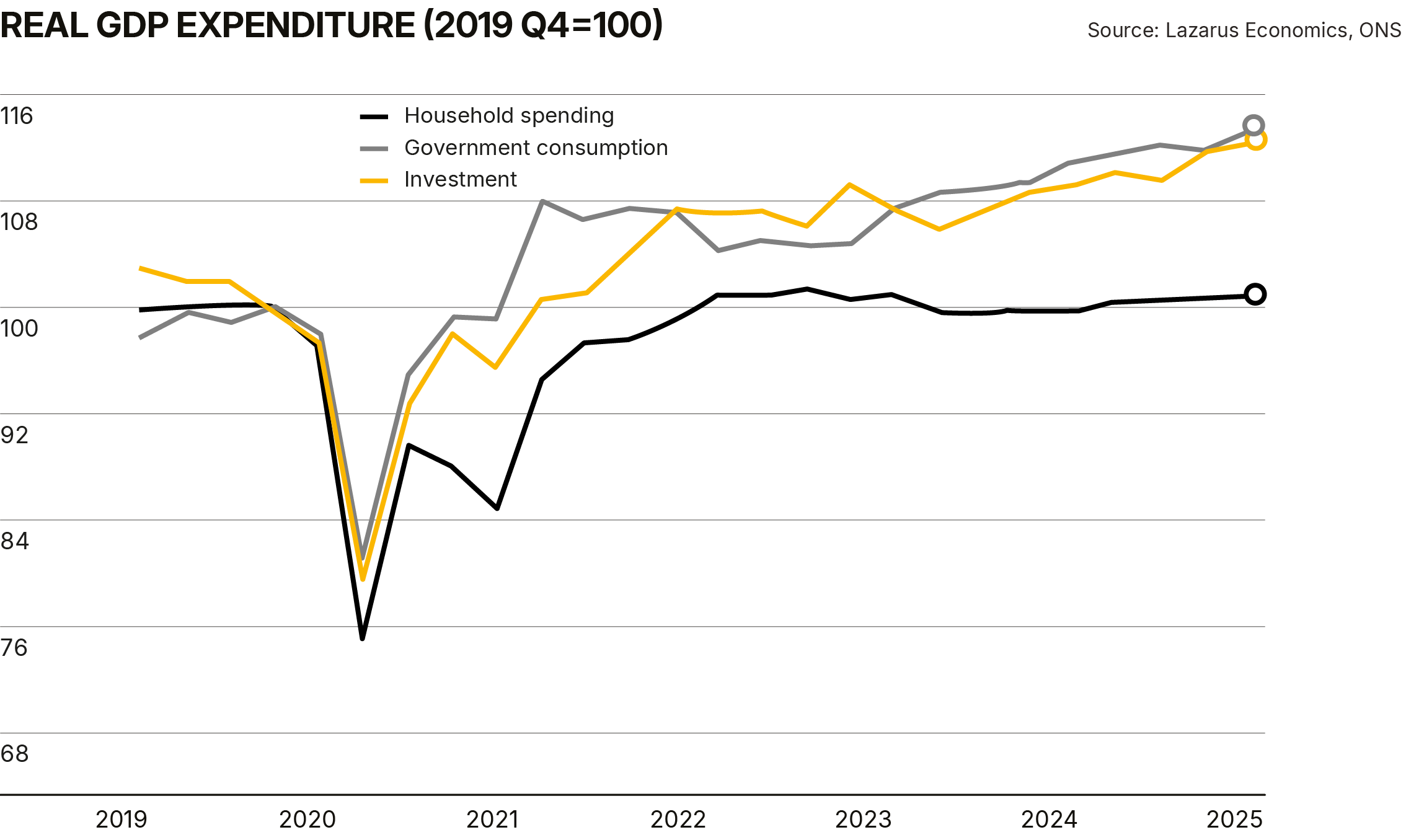

Looked at another way, total investment spending in real terms (public and private) since the pandemic has even kept pace with the rapid growth in government spending. What has lagged dramatically is household spending. There is no sign here of a dearth of investment in the economy.

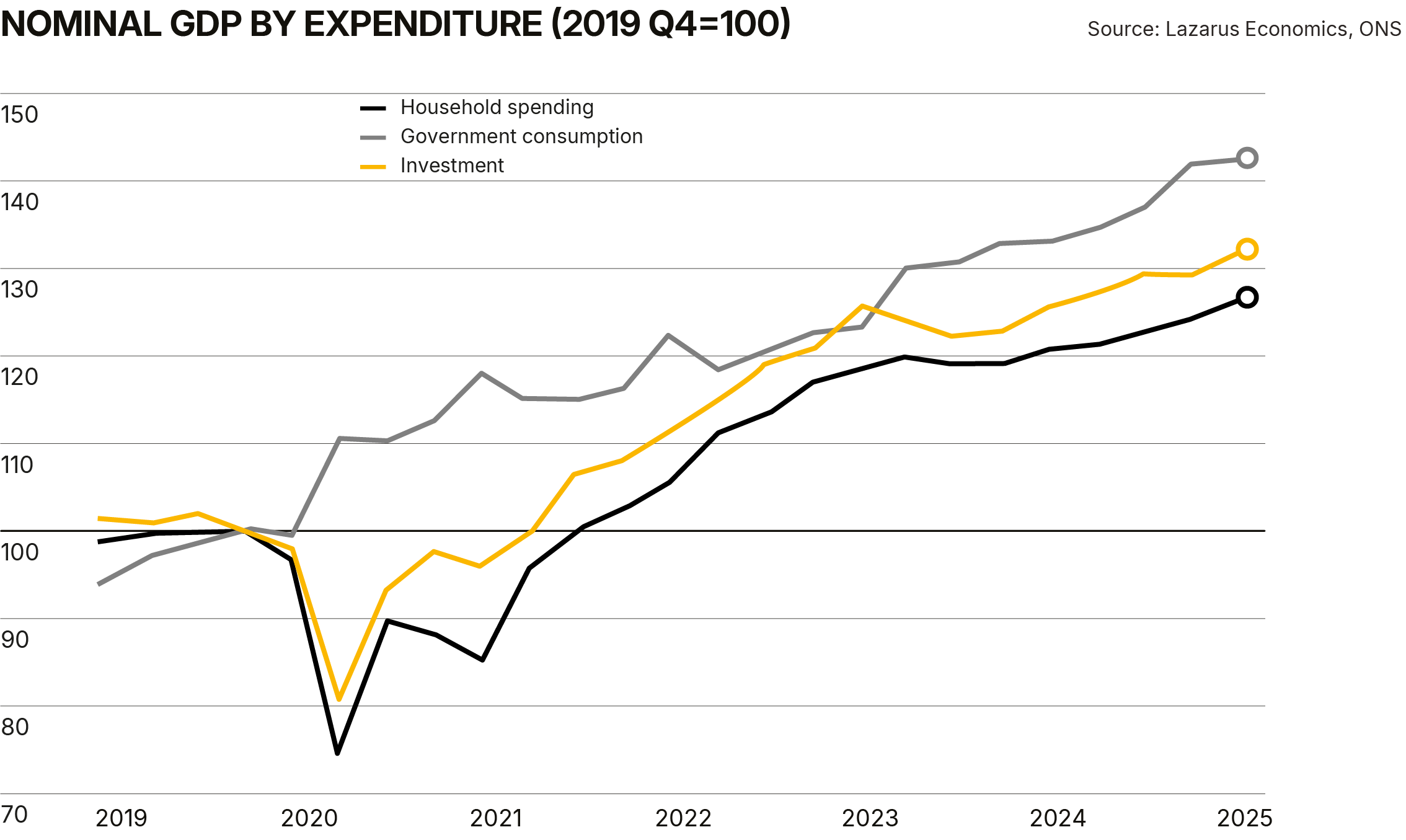

Here’s the same chart in nominal terms.

These charts have very important implications for the next bogus point the Chancellor made in her speech.

Low productivity / low growth

Those of you who have read my recent blogs on productivity may by now be bored to tears by this subject, but I will return to it here because once again it played a part in Ms Reeves’ speech as another reason for the “tough” decisions she will have to make.

Regular readers will know that the UK’s stats authority has had a very poor track record of measuring productivity historically. Current baseline productivity levels in the economy are unknown, and the five-year forecasts the OBR is currently mulling are the equivalent of looking for a black cat in a dark room that isn’t there.

Having said that, it is really interesting to look at the investment/spending chart above in the context of productivity.

What’s clear from this chart is that household consumption has lagged dramatically in the UK since the pandemic. In real terms, it’s about where it was in 2019. Just imagine for a moment what the growth outcome would have been had UK households copied what happened in the US and decided to spend rather than save. Growth would have been higher, and so would have productivity.

Fundamentally, this comes back to the point I have made in previous blogs: productivity is an output, not an input. It should be seen as the product of the relationship between the growth outcome and the labour input that delivered it. In my view, it should not be seen as a predetermined input that defines the economy’s growth outcome.

Either way, the track record of the UK’s measurement of this economic metric shows very clearly that, at best, there is a very loose determinative relationship between productivity and growth outcomes.

This chart maps the relationship between productivity and growth over a fifty-two-year period from 1972 through to 2024 (excluding the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021). I was particularly interested in the collection of dots (7), which shows that the economy grew at a time when productivity was negative. I was also intrigued by the four years when productivity grew, but the economy shrank. The most interesting of these is the year when productivity grew by over 4% but growth was negative.

For those mathematically minded, the R-squared of 0.2962 means that 29.6% of the variability in the dependent variable (growth) is explained by the independent variable (productivity). Importantly, the remaining 70% of the variability is unaccounted for by this relationship and is attributed to other variables or inherent randomness.

In other words, what the OBR is attempting to do – predicting UK growth by reference to future estimates of productivity – is so fundamentally flawed it’s dangerous.

What I now expect from the Budget

As we get closer to Budget Day, the leaks and rumours emanating from Westminster appear to be getting more precise and a bit more consistent, so much so that I think it’s now possible to get a reasonably accurate picture of what’s going to happen.

Given this slightly improved clarity, I thought that I should briefly outline what I think is going to be announced, not least so that readers can at least be armed with a reasonably well-informed perspective and be able to discount some of the more lurid speculation which has intensified in recent days.

Below are the headline measures that I think we can all assume will form the key revenue-raising measures in the budget. It’s worth saying again that none of this would have been necessary had the Chancellor decided not to be led by the OBR’s fundamentally flawed forecasts for productivity, but we are where we are and so have to confront the reality of this daft situation.

Why there is a “hole” to fill

Before outlining what I think will be the key revenue-raising measures in this budget, I should first outline what the key drivers are that lie behind the need to raise revenue in the first place.

- Government spending has increased significantly since Labour came to power, from an already elevated level inherited from the previous Tory administration.

- The government’s self-imposed fiscal rules mean that financing additional government spending by increasing borrowing over and above the plan is not an option

- Because the OBR has, bizarrely, chosen this moment to downgrade its forecasts for productivity growth over the next five years, and because, mistakenly, in my view, in the OBR’s world, productivity outcomes are determinative of economic growth, it has downgraded its five-year UK growth forecasts by about 0.25% per annum.

- This lower growth expectation leads to lower forecast tax revenues over this period, leaving a theoretical fiscal gap at the end, which the Chancellor apparently feels compelled to fill now.

The gap which these numbers appear to be leading to is somewhere just above £20bn (consistent with the numbers coming out of the IFS and the Resolution Foundation). So, not the £30-40bn number that has been doing the rounds for months, but more than my recent £10-15bn assumption.

The measures I expect

These are what I think the key revenue-raising measures will be as a consequence of this completely flawed process:

- The government will freeze all personal allowances – this raises about £10bn from all those with an income.

- Pension contributions from salary sacrifice (without incurring national insurance) will be limited to £2,000. This raises about £2bn.

- Gambling taxes will raise something like £1.5bn.

- A new tax on EVs based on mileage will be introduced to fill the gap left by the drop in fuel duty. A 3p-per-mile tax will raise, very roughly, about £0.5bn.

- A myriad of other measures (there are, in total, over 100 reliefs that cost the Government £200bn per year) which individually won't raise that much but collectively will plug the rest of the gap.

These measures in total will raise just over £20bn, so sufficient to meet the theoretical “hole” caused by the OBR’s downgraded productivity assumptions.

Some observations

The whole process for evaluating what the Chancellor needs to do on the 26th is fundamentally flawed for all the reasons I have outlined in detail above.

My guess is that this process will be seen as flawed as it becomes increasingly clear, over the next few years, that UK growth outcomes are far better than the OBR has predicted, which in turn will drive better productivity and better tax revenues. This might even lead to tax-cutting measures later in this parliament.

The scale of this £20bn tax hike will be characterised as extremely damaging to the outlook for the UK economy. As much as I do not agree with the arcane and flawed process which has led the Chancellor to this outcome, and as much as I believe the fundamental problem here is excessive government spending, I do not agree with this consensus conclusion. The tax increases will not help the economy, but neither do they represent a fiscal tightening either. Taxes have been increased in anticipation of a gap between taxes and future (planned) government borrowing.

Neither are the tax increases sufficient to derail what I believe happens next to the UK household sector. In very simple terms, my view is that lower inflation and interest rates will lead to lower saving and higher spending. In addition, higher lending growth will also help to drive higher consumption growth too. Remember that every 1% fall in the savings ratio, which is currently at a very elevated level (approaching 10.5%), adds about £20bn to consumer spending.

Unlike the MPC, and I suspect unlike the OBR, I also do not see business investment growth falling in 2026. The MPC have it falling from 4% growth this year to 1% growth in 2026. Quite why is not at all clear, especially in the context of the unfolding AI industrial revolution. Indeed, in the FT last week, there was a story that highlighted that a quarter of big businesses expect to cut jobs in the next year due to the impact of AI. A Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development survey found that 26% of large private businesses and 20% of public sector employers expect to have fewer staff over the next 12 months due to AI. So not only will businesses be investing in AI to facilitate this outcome, quite clearly, these same employers are expecting this investment to drive up productivity, ironically coinciding with the OBR’s clueless downgrade.

Conclusions

It’s hard to know where to begin. The pre-budget speech was pretty dreadful. It was all about politics and had very little to do with economics, as far as I can see. As an exercise in expectations management, it might work out because I still believe that the Chancellor will not inflict the sort of harm on the economy that most commentators, and certainly those who attended the press conference, appear to believe. (The questions were appalling.)

What was inevitable, I suppose, but nevertheless extremely disappointing, was the tissue of lies that the Chancellor resorted to telling to explain her impending “tough decisions”. The massive, unmentioned elephant in that room is, of course, the scale of government spending. It is the reason why she will have to increase taxes, and the rest of the waffle she came out with is just a smoke screen.

Despite this shocking situation and the lunacy I have already written about with respect to the OBR and its productivity forecasts, I remain upbeat about what happens next. In summary, my view is that the tax increases in the budget will not change my expectations for growth this year or next. In fact, I don’t expect this budget to have any impact on my growth assumptions at all, both for the remainder of this year and in 2026. For the record, that’s 1.5% for this year and over 2% for next. The MPC is forecasting 1.2% for next year, which looks to me, once again, to be bordering on daft.

I remain confident that the economic momentum, which is visibly building, will gather pace as interest rates continue to fall, and that lower rates will lead to a fundamental shift in UK household saving behaviour. Crucially, every 1% fall in the savings ratio adds about £20bn to consumer spending.

- Rachel Reeves is blaming Tory mismanagement, Brexit, Truss and “historic underinvestment” for a so-called fiscal black hole – most of which doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

- The real problem is the scale of government spending, not a lack of tax; the OBR’s downgraded productivity forecasts are based on a deeply flawed model.

- Those forecasts are now being used to justify roughly £20bn of tax rises – via frozen allowances, a basic-rate hike with an NI cut, and other stealth measures.

- I expect these measures to be damaging but not decisive: falling inflation and interest rates, lower saving and continued investment (including in AI) should still drive stronger UK growth than the OBR is forecasting.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.