Mental cleansing

As the year trundles to an end, I have decided to sign off 2025 with a slightly self-indulgent note. As regular readers will know, I have been frequently exasperated over the last twelve months by the relentlessly downbeat narrative in the media and the all-too-frequent scare stories about the state of the UK economy, which have not only been alarmist but also profoundly wrong.

It’s not healthy to hold grudges, even economic ones, so this note is an exercise in letting go of the things I have found most annoying in 2025.

The ONS

I will have to forgive the ONS (Office for National Statistics) for being unable to measure what’s going on in the economy accurately.

The government appears to believe that changing the ONS’s leadership will bring about some miraculous improvement in its performance, but I suspect the problems go far deeper than the leadership team.

My advice would be to focus on what it knows it can measure accurately and to completely rethink the things it knows it can’t, like GDP every month by reference to output measures, or the Labour Force Survey, which has been giving a misleading picture of employment for months.

The OBR

I will have to forgive the OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility) for being way too gloomy again, and for basing its five-year growth forecasts on a flawed relationship between guesses at UK productivity and GDP outcomes.

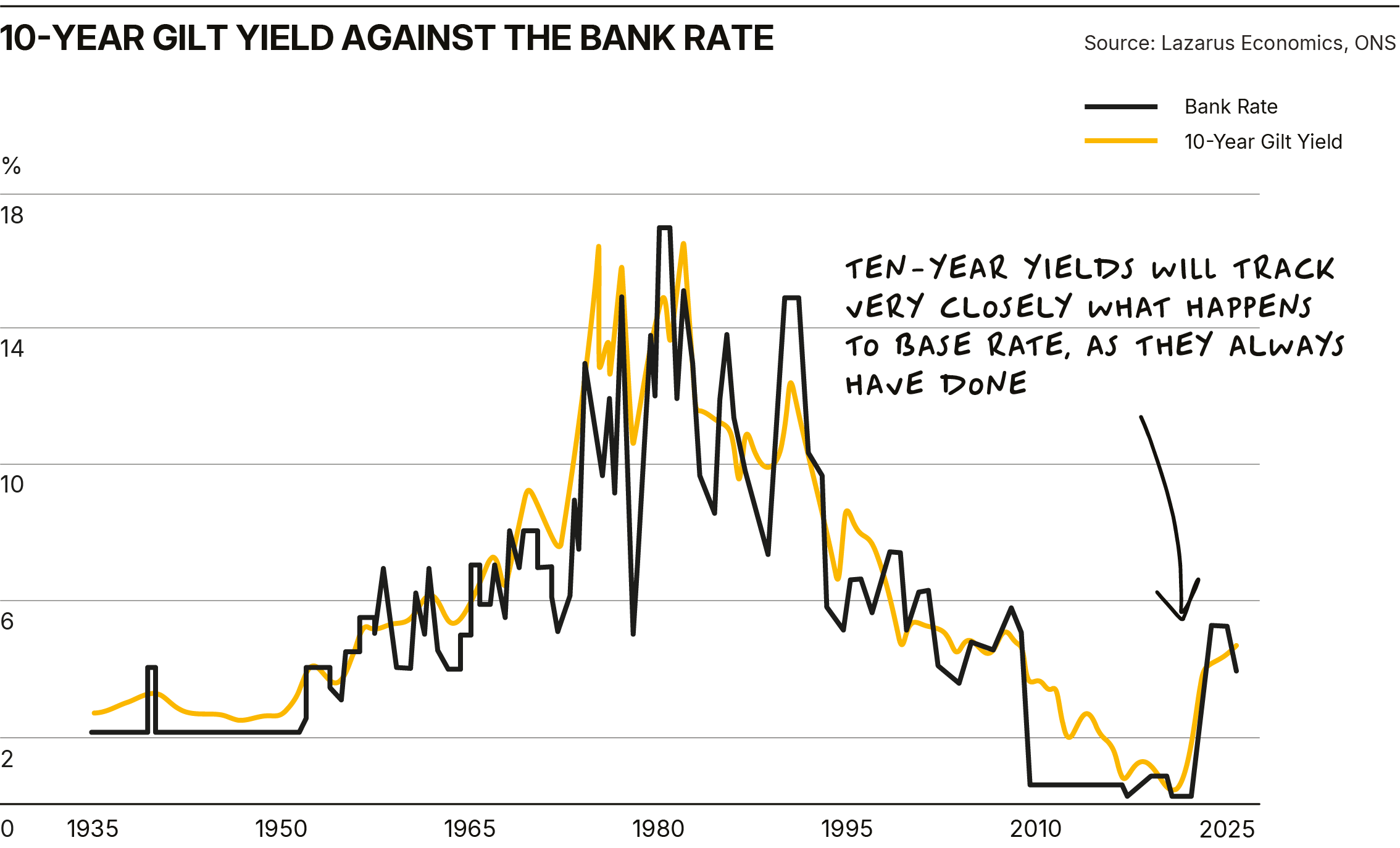

I also have to get over the OBR’s very strange forecasts and the “conditioning assumptions” it uses. This methodology has once again revealed some very weird expectations underneath the headline numbers. For example, the 2% wage growth and 2% inflation forecast for the five-year period, alongside a 5% ten-year gilt yield and a 5.1% mortgage rate assumption.

The chart below should be sufficient to highlight why that is just wrong. By implication, what the OBR seems to be suggesting is that UK inflation will be at 2% but base rates will be somewhere close to 5% on average from 2026 through to 2030—utter madness.

NIESR

I will also have to get over my irritation with the NIESR (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) and all the media and economic commentators that took its original £50bn black hole prediction and concocted a mountain of horse manure about what would have to happen to taxation to fill it.

What we now know is that the OBR’s downgraded productivity forecast, in 2029/30, resulted in the Chancellor’s fiscal headroom being £4bn rather than the £10bn predicted in March. In other words, a “black hole” of £6bn, not the £50bn the NIESR had forecast. I said at the time that this was nonsense, and so it proved to be.

I am not expecting an apology from the NIESR nor from the chorus of doom-laden forecasters who swallowed this black hole narrative, despite the fact that the pre-budget speculation clearly harmed the economy, which, according to the ONS, has flat-lined in the months leading up to the budget announcement. For future reference, we should all remember that this institution, and many others like it, has an appalling track record of accurately forecasting the economy. My advice is to ignore its next dire forecast completely.

Productivity "experts"

I also need to move on from the frustration I feel every time I hear an expert or politician opining on why the UK economy has a productivity problem. Undoubtedly, the public sector, and in particular the NHS, has a massive productivity challenge, but I don’t believe this widely held view about the private sector is true, not least because the ONS can’t accurately measure the economy’s output or the number of people employed in producing it.

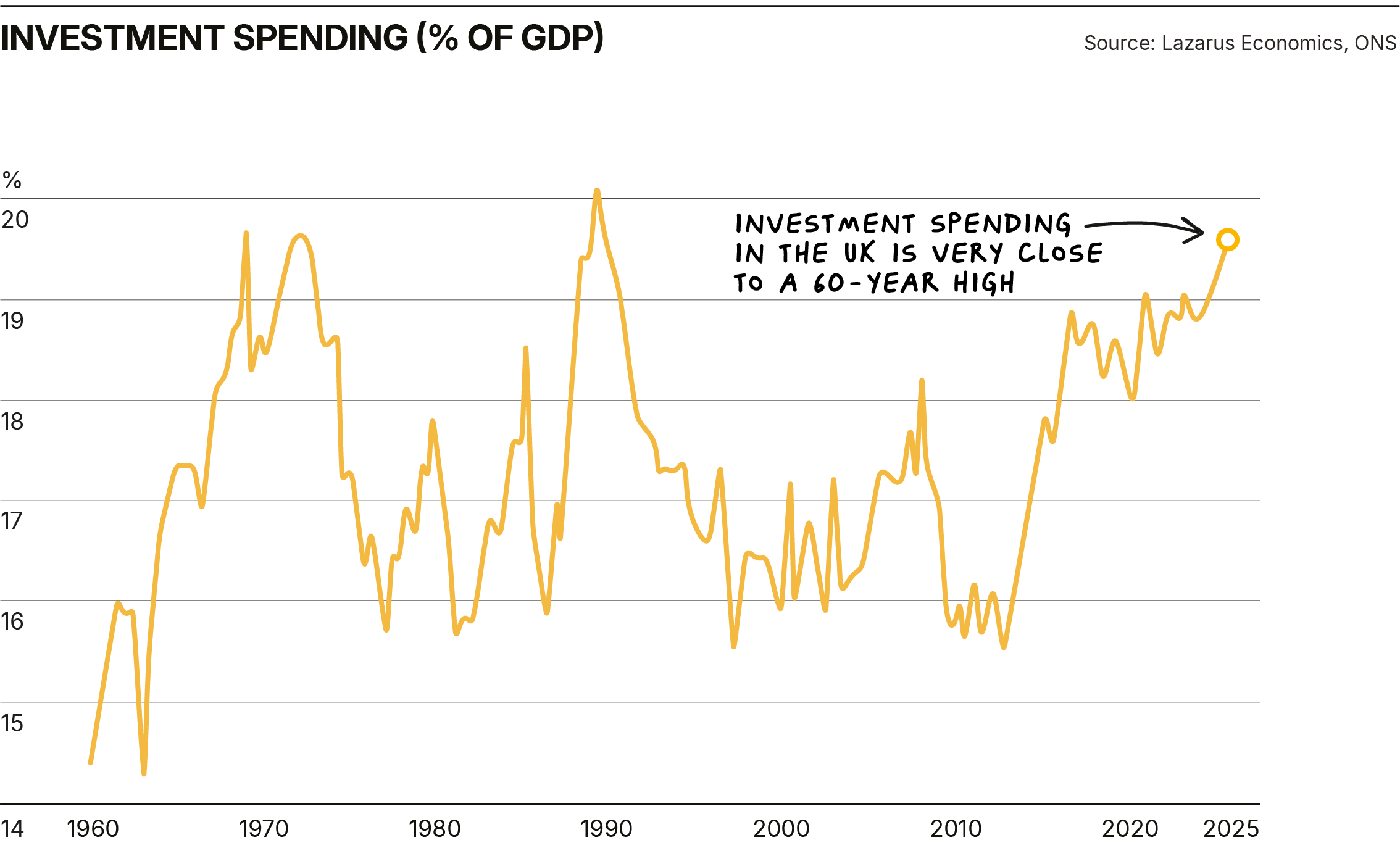

But more than this, the cause of this apparent low productivity in the UK, namely “chronic underinvestment”, is also a myth, as the chart below demonstrates. What it shows is investment spending in the UK very close to a 60-year high, which, when adjusted for the low share of manufacturing in the economy, compares very favourably with all of our G7 peers. (For the record, the more capital-intensive manufacturing sector accounts for about 9% of GDP in 2025, back in 1990 it was about double this, and in the early 70s it was over 30% of GDP.)

The MPC

I will also have to forgive and forget the fact that the MPC (Monetary Policy Committee) has once again failed to accurately forecast UK economic performance by being way too gloomy. (It is again for 2026). Thankfully, it does appear to be paying less heed to its broken model and relying more on judgment, which is something Ben Bernanke recommended in his review of its forecasting record.

The problem is that the judgment of too many of its members is fundamentally flawed. Instead of pragmatism, most members of the committee, because they are academic economists, focus on unmeasurable concepts like inflation expectations, capacity utilisation and R* or the neutral rate of interest. This is the rate of interest that neither stimulates nor restricts the economy. Sounds good in theory, but the problem is that no one knows what it is, and even the Bank Of England (BOE) accepts this when it says that R* is in a range from 2-4%. That’s about as useful as a chocolate fireguard.

I was also amused to learn this week that the BOE's inflation expectations data, widely considered important in framing policy decisions, is calculated from 1,000 to 2,000 responses to the Household Inflation Expectations Survey, conducted quarterly. That’s about 0.005% of the 29 million households in the UK. Hardly a representative sample.

It appears that in 2026, I will have to overcome my ongoing frustration with the BOE and the MPC, their forecasting record and policy errors. Perhaps the MPC's decision to cut base rates by 0.25% last week should be considered as recompense or an early Christmas present.

As for the rest...

I could go on, but my compassion is by now exhausted.

I was intending to forgive Ed Miliband for his lunatic energy policy, and Rachael Reeves for lying to the country ahead of the budget, and to all the scaremongering media for writing so much nonsense about the performance of the UK economy, and for failing to acknowledge the performance of the UK stock market in 2025.

Those grudges I will carry into 2026, but I hope that by this time next year I can be acknowledging their respective about-turns and congratulating them for removing the scales from their eyes!

I live in hope. Happy Christmas to all our readers!

This is a deliberately self-indulgent end-of-year note — an attempt to clear the mental clutter after twelve months of relentless economic scaremongering that turned out to be largely wrong.

I forgive the ONS for its inability to measure key parts of the economy accurately, particularly productivity, employment and monthly GDP. These aren’t small errors; they materially distort the national conversation and policy decisions. Changing leadership won’t fix that — the problem is structural.

I forgive the OBR for once again producing gloomy five-year forecasts built on deeply flawed assumptions about productivity, wages, inflation and interest rates. Forecasting 2% inflation and wage growth alongside 5% gilt yields and mortgage rates is simply incoherent. It reflects a model divorced from economic reality.

I forgive the NIESR and its fellow doom-merchants for conjuring a mythical £50bn fiscal black hole that never existed. The reality was closer to £6bn. The damage caused by months of pre-budget hysteria was real, yet no one involved has apologised — nor will they.

I reject, again, the lazy narrative that the UK’s private sector suffers from chronic underinvestment. The data shows investment near a 60-year high, and when adjusted for the shrinking size of manufacturing, it compares well with G7 peers. The productivity “problem” is far more about measurement failure than economic weakness.

I remain exasperated with the MPC’s forecasting record and its obsession with unobservable concepts like R* and inflation expectations derived from tiny, unrepresentative surveys. The Bank is at least starting to rely more on judgement, but too often that judgement is still flawed.

Some grudges — energy policy, political dishonesty, and media misrepresentation — I will carry into 2026. I hope that by this time next year I can be acknowledging their respective about-turns and congratulating them for removing the scales from their eyes!

I live in hope. Happy Christmas to all our readers!

Noise Cancelling Podcast

If you enjoyed this, you’ll find more of the same thinking on the Noise Cancelling podcast. Each week we cut through the headlines, challenge lazy consensus views, and focus on what actually matters for markets and the economy. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.

Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

2026 Global Economic Outlook

If you haven't already, you can download a copy of my Global Economic Outlook for 2026 here.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.