Global Equity Market Update

UK

In common with all other global indices, the UK equity market had a major wobble in April following President Trump’s tariff announcement at the beginning of the month. In the space of just over two weeks, the FTSE 100 fell by over 11% but has since recovered all of that slump. In my opinion, it now stands poised to make further gains through the remainder of the year despite the headwinds created by the aftermath of the tariffs and much lower oil prices, which have negatively impacted two of the largest listed businesses in London, BP and Shell.

Despite today’s reticence from the MPC (see below) which has only cut rates by 25bps, the prospect of more cuts to come through the remainder of the year combined with better sentiment following the trade deal with the US, should provide an improving backdrop for the UK equity market which I expect to continue to outperform other global equity indices based on its outstanding valuation attractions. I would also expect to see further outperformance of those sectors focused on the domestic economy, where, in general, company results are on an improving trend, but also where the valuation attraction is greatest. For example, in the financial sector, all three large domestic banks, Barclays, Lloyds and NatWest, announced consensus-beating Q1 numbers in the last month. In the housebuilding sector, there are clearly signs of a significantly better trading environment gradually emerging. Specifically, Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey both reaffirmed higher completion expectations for the current financial year alongside flat input prices and modest house price inflation. Elsewhere, amongst the domestic economy-facing sectors, a number of retailers, including Next and Tesco, have also announced better-than-expected numbers.

I should emphasise that these results do not provide unequivocal evidence of a better-performing economy, but the probability of a much better outcome in the UK than is predicted by the consensus is definitely building. In some ways, what the MPC has said today confirms this better outlook (more below) despite the more cautious headlines accompanying its rate decision today.

Finally, to the UK gilt market. For a while, I have been saying that bond yields would fall through 2025 and not rise as the OBR anticipates. After a wobble earlier in the year, this is precisely what is now happening across the world’s government bond markets. Ten-year yields in the UK are now just above 4.4%, and I expect them to fall further to 4% and possibly below later in 2025.

Last week’s rate decision

Last week, the MPC announced that UK base rates will fall by 25bps. This was what was widely expected. Recently, I have argued in several blogs why rates needed to come down in the UK, and I had hoped for a more significant cut today. The outlook for rates, in my opinion, remains the same. They will continue to fall from their current level of 4.25% down to 3% in about a year’s time, in part tracking the clear path I see for UK inflation, which will return to target later this year or early next year.

Having said that, I can’t resist the temptation to pull apart what the MPC has said today, not least because much of the commentary that has accompanied the decision is impenetrable nonsense.

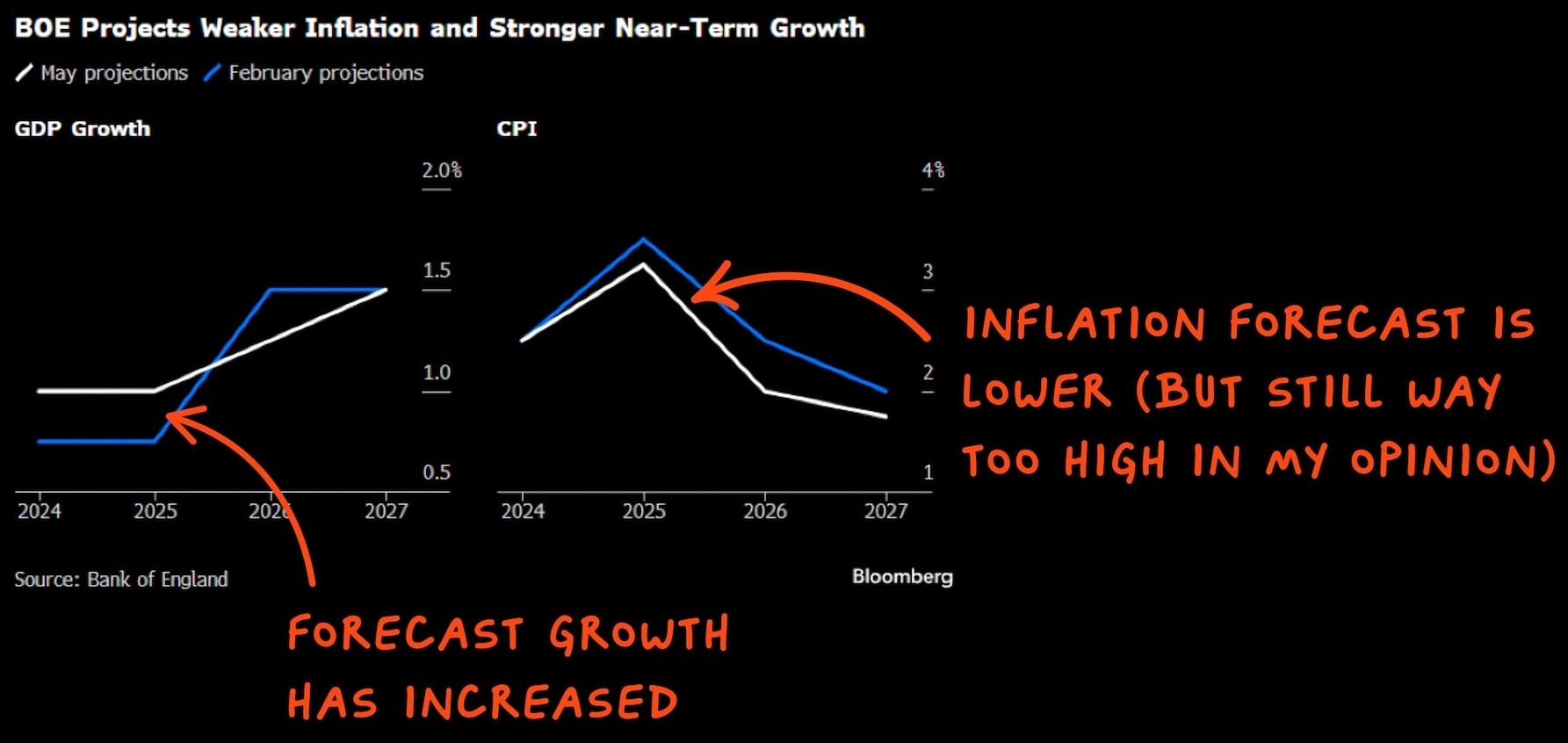

First, to the MPC’s growth and inflation forecast. Amongst all the guff, there is what I had anticipated, which is a higher growth forecast for 2025 and a lower inflation forecast. The forecast for growth has increased from February’s 0.75% to 1% for 2025, and the inflation expectation is lower, although still way too high from April through to the end of the year. (see chart below)

Before commenting on some of the contradictory nonsense in the accompanying narrative to the decision, I should say that the growth expectation is still too low for 2025 in my judgement, and the inflation forecast is still too high. I expect the economy to deliver close to 1.5% growth and that inflation will peak at somewhere close to 3% in April and fall significantly thereafter. In my view, the committee’s downgraded growth forecast for 2026 is also wrong. I expect the economy to accelerate in 2026 and to deliver something in excess of 2% growth next year. (I should point out that the MPC and OBR are now quite far apart regarding their 2026 growth forecasts. The MPC is at 1.25% and the OBR at 1.75%, which begs the question of why we have these two important policy bodies developing different forecasts with presumably different models. Which one is the government to believe, I wonder?)

Whilst I am at it, I thought that I should also highlight yet another revision of recent history which I am confident will receive absolutely no attention in the media but which once again shines a light on the volatility of trade data and its consequential impact on what the MPC and OBR tell us about what is going on in the economy.

Back in a blog I published on March 6th this year, I showed why the Bank of England had downgraded its growth forecast for the UK economy (I said it would have to upgrade later in the year, which it has done today). At the time, the biggest single explanatory factor in the Bank’s downgrade was a change in its forecast for the contribution of net trade, which went from minus 0.75% in November 2024 to minus 1.5% in February. I said at the time that this was an especially noisy and volatile series and although this change was largely responsible for the Bank's downgrade, it would likely be significantly revised. Well, surprise, surprise, that is precisely what has happened today. The Bank’s forecast for the contribution from net trade has decreased from minus 1.5% to minus 0.5%. Once again, this significant change has received no attention, which is especially odd on a day when the Bank is keen to tell us that the biggest threat to the economy is an unspecified trade impact due to Trump’s tariffs.

There are also some perplexing comments from the governor and from members of the committee that sit alongside this decision, which was far from unanimous. Indeed, two members of the Committee wisely voted for a 50bps reduction, but two others voted for no change. Let me give you a few examples:

- The committee upgraded its 2025 growth forecast (and downgraded 2026) but at the same time said that the sharp 0.6% increase in GDP in Q1 was largely accounted for by “erratic factors” as sales were brought forward to avoid tariffs. The statement suggests that the underlying growth rate in the first quarter was “around zero”.

- The committee was clear that the main threat to the UK was from the global impact of US tariffs on the UK’s open economy.

- Catherine Mann, who two meetings ago had voted for a 50bps cut, decided this time that no cut was advisable because of “inflationary persistence due to supply-side problems in the UK.”

- The committee accepted that even after the 25bps cut, rates are still effectively “bearing down” on growth and inflation, while the risk to growth is “somewhat to the downside”.

In effect, the committee has said that the strong growth in Q1 was an illusion and that “underlying “growth was close to zero. So, given that the economy flat-lined in the last six months of 2024, the last nine months have seen virtually no growth in the UK economy, according to the MPC. If they really believed that, why did they not cut by more?

Although the MPC mentioned “underlying growth”, they didn’t specify what this meant. I am also perplexed by the comment that sales were brought forward in Q1 to avoid tariffs. My question is, what tariffs were being avoided? The UK government has announced no tariffs on any goods, and indeed, since April 2nd, has been speaking about trade deals with the US and India. I am also wondering how this mythical tariff avoidance could possibly affect the sectors that were stronger than expected in Q1. In particular, construction and services output were both significantly better than expected in Q1, but neither sector is affected by tariffs. Very odd.

The committee discussed tariffs as the main threat to the UK economy on the same day a comprehensive trade deal with the US was announced. The irony of this, I hope, is not lost. In summary, I completely disagree with the committee. I have previously written about the irrelevance of Trump’s tariffs on the UK economy and would add that, in my opinion, the biggest threat to UK growth is the failure of the MPC to get rates to a sensible and appropriate level.

Catherine Mann’s erratic voting is somewhat perplexing, too. At the last but one meeting, she voted for a 50bps cut. Since when, according to the committee, the economy has flat lined in “underlying” terms. But this time she voted for no change, citing inflationary persistence due to supply-side problems in the UK. Why were these same supply-side issues not relevant to her back in February? Surely, the unmeasurable supply potential of the economy cannot have changed in less than three months, so why the dramatic change in her voting? Again, very odd.

Finally, to the committee’s summary that rates are effectively “bearing” down on growth in the UK (and inflation) and that the risks to growth are to the downside. Again, if the committee believes this and also believes that the economy has effectively not grown for 9 months, why did it not cut rates by more than 25bps? (After all, the ECB has cut rates to 2.25% and yet the EU economy has the same inflation rate as the UK)

None of this makes sense to me. As usual, the MPC’s May 2025 Monetary Policy Report is very long and full of interesting data and detailed analysis, conditioning assumptions, and other detailed analyses, but to my eye, totally inconsistent. It is, yet again, another great example of arcane complexity and rubbish judgement. The committee’s conclusions on underlying growth and inflation are not at all consistent with its decision, and its fears about tariffs are inconsistent with reality. As a result, it is still, in my opinion, way too pessimistic on both. The pages of academic mumbo jumbo dedicated to unmeasurable concepts such as excess supply, capacity utilisation, the output gap and potential GDP may be interesting but useless in guiding the appropriate policy decisions the committee is charged with making. Again, the comparison with the pragmatic simplicity of what the FED says and how it explains its decisions could not be more stark.

Nevertheless, we are where we are and at least we have a cut in rates to welcome. More will come later in the year, but once again, I lament the Bank of England’s hopeless forecasting record, its love of complexity and academic economic nonsense, and hope that one day it recognises that there is a better, more pragmatic and helpful way to set monetary policy here in the UK.

A small aside...

I thought it might be worth explaining why I am so scathing about academic concepts like potential supply and demand and inflationary and deflationary gaps, which are the sorts of things that the academic economists on the MPC seem to obsess about. The context here is, as we already know, measuring what is actually going on in a complex economy like the UK is challenging. It is clear that the ONS has been struggling for a long while with the measurement of basic things like population, immigration, output, productivity, and trade data, and so much so that the ONS’s regulator has announced that the ONS must take decisive action to restore confidence in its economic statistics, particularly in its survey operations. My point is, if it is as challenging as it appears to be to calculate these basic things, how valuable is the attempt to measure supply potential, the output gap and capacity utilisation? All may be interesting academic concepts, but they are impossible to accurately measure in a real, complex economy like the UK. They should not feature in judgements about what’s actually happening, nor should they inform policy decisions.

If any readers doubt what I’m saying, I would advise them to think about what the potential supply of the business that they work in is, or indeed what the actual supply of that business is. My guess is that readers will not have a clue what either of these numbers would be or indeed how to measure these concepts. I certainly wouldn’t know where to start, either.

US

The US equity market has once again confounded the consensus view that the Trump tariffs announced on April 2nd would lead to a significant and sustained correction, which would later be reflected in the economy sliding into recession. I suggested at the time that the market’s initial reaction was completely overblown and continue to believe that the US economy will deliver reasonably good growth in 2025 and 2026, albeit at a slower pace than in 2024.

Having said that, I do not underestimate the near-term disruption that this chaotic month has created in US boardrooms. Clearly, for some sectors, it has been a very difficult period, but again, as I wrote at the time, the initial announcement was likely to represent the worst possible outcome and that through a process of negotiation, the initial tariffs would be ameliorated significantly. It is also clear that Trump has also blinked on numerous occasions in the last four weeks as the potential impact of his initial proposals was revealed in numerous engagements with leading figures from corporate America.

In previous blogs and updates, I have written about how different companies, sometimes in the same sector, have responded in different and unusual ways to the original announcement. Whilst the dust continues to settle in this 90 day window in which many deals are likely to be done, the latest announcement which reveals that China and the US will be sitting down to talk to each other in Switzerland this weekend, highlights once again that the simplistic and alarmist initial reaction to the announcement was yet another great example of how markets can get things very wrong from time to time.

I still believe that the US stock market is overvalued and will continue to underperform other, much cheaper global equity markets, potentially for an extended period. Within the US market, however, there are pockets of extreme undervaluation in some notable sectors, including semiconductors, healthcare, and renewable energy. In general, all of these have performed poorly in recent weeks. This, I believe, has created an even bigger anomaly in these unloved and under-appreciated areas of the US equity market.

Tariff fears have been the principal concern in the semiconductor sector. Trump's tariff agenda has undermined confidence in the renewable energy industry and most recently, the appointment of a new head of the FDA has undermined what little confidence remained in the US biotech sector, which has had an especially torrid 2025 following more than two years of relative underperformance. My guess is that the now extreme undervaluation of these sectors will eventually catch the attention of US investors and that their performance will improve significantly, but, as ever, the precise timing of this renaissance is impossible to accurately predict.

China

Following the Liberation Day mayhem that President Trump unleashed on the world just over a month ago, things have gradually calmed down and a sort of “back to normal” mood has started to regain some currency. In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s original tariff announcement, the Chinese equity markets fell significantly, in common with virtually all other financial markets. It has since recovered well but is still just over 4% below its late March peak. (CSI 300)

In part, this is a product of concerns that the extremely damaging tariffs levied on Chinese exports will remain in place and lead to significant damage to the domestic Chinese economy, especially to the manufacturing sectors geared into the lucrative US export market. These concerns are reflected in a number of high-profile downgrades to growth forecasts for the Chinese economy, notably from the IMF and a range of leading global investment banks.

Policy makers in China have sensibly responded to the tariff announcement by introducing a package of mainly monetary measures designed to stimulate the domestic economy and to provide targeted help to those businesses and industries directly affected by the trade war with the US. These measures include lower reserve requirements for commercial banks (to enable them to lend more), a significant injection of liquidity, lower policy and mortgage rates and a series of measures designed to help foreign listed companies return to China’s domestic stock markets. This is an important package of measures, but I am confident that further fiscal policy announcements will be targeted at the household sector to encourage less saving and more spending in the near future.

Before this important policy announcement, it was also revealed that the first serious trade talks will occur between the US and China in Switzerland over the weekend. I had expected this to happen, and albeit a little later than I had hoped, I believe it will eventually lead to a significant amelioration of the current proposed level of tariffs and trade restrictions on both sides.

Prior to the disruption caused by Trump’s Liberation Day announcement, I had a very positive view of the domestic Chinese equity markets and specifically of some of China’s leading technology and EV businesses, nearly all of which to me looked profoundly undervalued after years of underperformance. Despite the additional potential challenges now confronting the Chinese economy, which of course may ease through the next period of negotiation, I am confident that the appeal of some of these leading Chinese stocks remains undiminished. Indeed, in some cases where share prices have performed poorly, their appeal has, if anything, increased.

If the policy stimulus starts to yield the results the leadership hopes for, then this recent setback will quickly fade, and I expect the market to start performing again, just as it did in the earlier part of 2025.

Trade negotiation update

Very encouragingly, it has been announced that the trade discussions between the US and China, which took place in Switzerland over the weekend, went very well. This morning, in a joint statement, both sides announced that they will temporarily lower tariffs on each other’s goods imports. The combined 145% US levies on most Chinese imports will be reduced to 30%, including the rate tied to the fentanyl issue, and the 125% Chinese duties on US goods imports will drop to 10%. This major de-escalation move is one I had hoped we would see, and it gives both sides three months to resolve their differences more fundamentally. Significantly in relation to the work still to be done, Scott Bessant said, “We are in agreement that neither side wants to decouple”.

Much work still needs to be done to secure a lasting agreement between China and the US, but this is a good start. As for financial market reaction, the Pavlovian initial response, oil up, bonds down (yields up) and equities up, is broadly what one would have expected. However, my guess is that a more considered response may lead to lower bond yields as the inflationary fears associated with very high tariffs abates. I would also expect further upside in equity markets, especially in China, where tariff uncertainty has been most acute.

Markets are recovering from the April tariff shock faster than expected but not uniformly, and not without continued confusion from policymakers.

In the UK, equities have regained lost ground and now look well placed to outperform, particularly in domestic sectors like banks, house builders, and retail. A 25bps rate cut from the MPC was welcome but underwhelming. The accompanying commentary (full of contradictions and academic abstraction) remains as muddled as ever. Growth and inflation forecasts have improved, just as I predicted, yet the committee still lacks the conviction to act decisively.

In the US, the recession many confidently forecasted hasn’t materialised. I still expect steady, if slower, growth in 2025 and 2026. But within the broader market, which I view as overvalued, there are deep valuation anomalies in semiconductors, renewables, and biotech. These sectors remain under-owned and under-appreciated, largely due to tariff noise, energy policy confusion, and regulatory inconsistency. That won’t last.

In China, policymakers have responded with a serious and targeted stimulus package. Trade talks with the US have started and already produced a major de-escalation in tariffs. Despite some ongoing uncertainty, I remain positive on China’s equity market — particularly in select tech and EV names, where valuations look increasingly compelling.

The consensus misread the moment. The data and the direction of travel suggest something more constructive.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.