Catch 22 – can we escape?

When reading through the predictable and unquestioning press coverage of NIESR’s latest UK fiscal projections, I was reminded of this novel and its central theme: being trapped by contradictory rules. I will try to explain the analogy, which is not perfect, with the current hysterical debate about fiscal black holes, but I hope you will see the connection.

In his famous novel, Joseph Heller describes how US aircrew during the second world war who were subjected to a medical evaluation to assess their fitness to complete more missions, were trapped by the dilemma that in seeking a mental evaluation for insanity – hoping to be found not sane enough to fly – demonstrate their sanity by so doing and in turn fitness to keep flying. I found it a pretty depressing read, as I do in a very different way, when I wade through the coverage of the latest economic doom authored by NIESR, the UK’s longest-established economic forecasting body.

In its latest projections, the NIESR has said that Rachael Reeves must increase taxes or cut spending by over £50bn to plug a hole in the budget arithmetic. The debate has naturally moved on to which taxes will be increased or allowances frozen to raise the necessary revenue, given that spending cuts are now deemed impossible, given the recent Labour backbench rebellion over disability benefits.

I fear that this debate will have precisely the same effect as Rachael Reeves’ dire projections did last year when the incoming administration sought to pave the way for its tax-raising budget in October. In summary, the economic momentum that had built up in the economy in the lead-up to the election was effectively crushed by a downbeat narrative and by the budget measures themselves, which came into effect in the first half of this year.

Critically, the financial media have once again decided to parrot the NIESR numbers in their desire to peddle the most alarmist stories about the economic future rather than try to understand how NIESR got to this number in the first place, what assumptions lie behind its projections and over which period this black hole emerges.

Before attempting to do that, I wanted to cover some facts about government borrowing, its current level, and its projected future growth based on the OBR’s existing forecasts, which, like NIESR’s, go out to 2029/30.

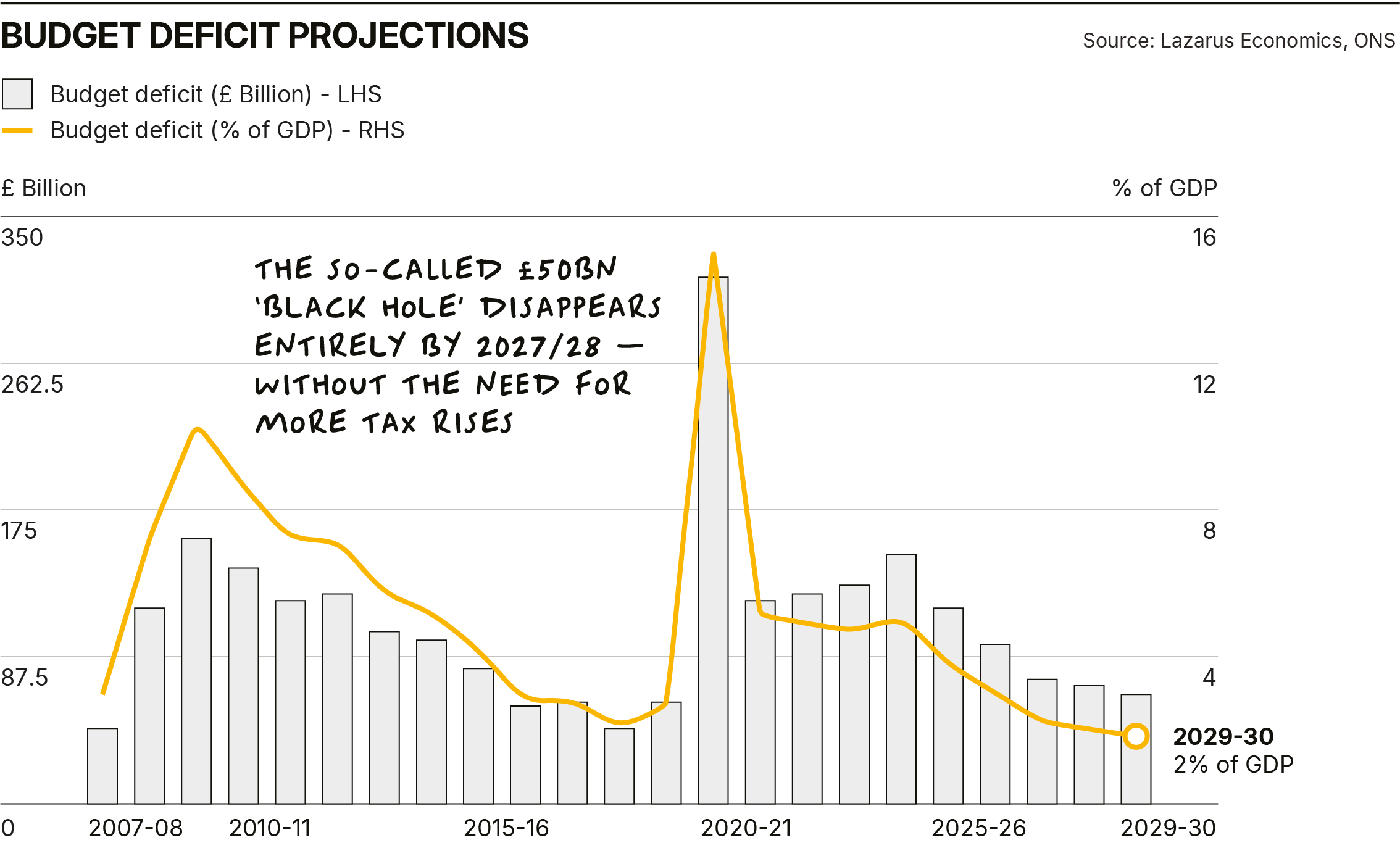

So, the UK’s budget deficit was just under £150bn in the 2024/25 financial year. That’s 5% of GDP and a bit higher than the previous year. Government spending in the most recent financial year ended up being £60bn higher than was forecast under Rishi Sunak’s government in the March 2024 budget. In this financial year, the budget deficit in the first quarter increased by £7.5bn on the same period in the previous year, and at £57.5bn, was exactly in line with the OBR’s latest forecast.

Looking forward, with tax receipts growing strongly (after last October’s tax increases) and spending growth slowing, the budget deficit starts to fall in the second half of this year and into next year. For this financial year, the budget deficit is forecast to be 4% of GDP, and the current budget deficit, which excludes investment spending, will fall to 1% of GDP.

Looking further out and based on a combination of the OBR’s forecasts and those of my favourite economist, from 2026/27, growth in spending at 3% is expected to lag growth in tax receipts at 4%. Based on these numbers, the budget deficit continues to fall to around 2% of GDP by 2029/30, and the current budget moves into a surplus from 2027/28 onwards. Consequently, based on what I believe is an appropriate and relatively cautious assessment of the outlook for the economy over this period, the government meets its fiscal rules without the need for further tax increases in the Autumn Budget.

However, this is not what NIESR believes and presumably, what most of the media are at least happy to repeat. And to remind you of the numbers, NIESR says that a £50bn hole has emerged in the public finances and that tax increases are required to fill it. As far as I can see, though, no one in the media has asked the crucial question: what forecast is this judgment based on? The answer is that these numbers are simply the product of much more bearish growth expectations over the forecast period than the OBR’s, the Bank of England’s, or indeed that of my favourite economist. According to the NIESR, UK growth will reach an uncontroversial 1.3% in 2025, fall to 1.2% in 2026, and fall further to about 1.1% over the next four years, which is half the UK’s long-term historic growth rate. The cause of this depressingly low forecast is, in summary, (from my reading of NIESR’s Summer 2025 UK Economic Outlook) a forecast for business investment growth that is under half the average of the period from 2010 -2019, no real fall in a currently very elevated savings ratio, limited real earnings and consumption growth and a pretty bleak outlook for exports, which they say will be badly impacted by Trump’s tariffs, which interestingly don’t seem to affect the Institute’s forecast for the UK’s demand for imports.

Interestingly this bleak assessment of the UK’s economic outlook comes just after the Bank of England increased its forecast for growth this year by 0.25% to 1.25% and which also saw its World GDP forecast increase from 2.5% to 3% for this year, on the back of a less silly forecast for the impact of Trump’s tariffs on global growth than the Bank of England had back in May.

If I were critiquing the NIESR forecast, I would start with its gloomy investment spending growth number and then focus on its expectation that saving remains elevated even while interest rates continue to fall. Under their own forecasts, real wage growth remains positive at about 1.25% pa. In summary, I think something structural must have gone awry in the economy if its five-year growth number is going to average half its long-term outcome, and yet the NIESR report fails to identify what that is.

So, to return to the Catch 22. In my mind, we are in danger of being trapped just as Heller’s aircrew were by an emerging dilemma. The more the media laps up the doom-laden forecasts of the UK economy and their implications for fiscal policy without questioning their underlying assumptions, the more the negative narrative will depress consumer and business sentiment. The depressing growth outcome will be assured as consumers, in particular, hold back consumption and increase their savings in anticipation of the “inevitable” tax increases.

I suppose I am fearful of the economy totally unnecessarily talking itself into a lower growth, higher tax outcome. As it is, unlike the financial media, I am sure that Rachael Reeves hasn’t completely swallowed this narrative and is equally alive to the fact that growth in the economy is the number one priority.

She will need the OBR’s updated forecasts to finalise her plans for the Autumn budget, but my guess is that there will be some tax increases announced for example on gambling and a further freezing of income tax thresholds, but not the panicked fiscal measures advocated by NIESR and parroted by the media that would, I fear, create the outcome that they may have forecast but from which we would all suffer. If I were advising the Chancellor, I would advocate a little more bravery and decisiveness, which should involve telling us what she might do, but importantly, what she won’t. The alternative is to be led by an ill-informed media mob interested only in alarmist headlines rather than informed analysis. This is the path too many politicians and chancellors have been led down in the past, and it doesn’t end well.

A more rational outlook would see a UK consumer emerge from its shell after enduring the pandemic, an energy price crisis and its impact on inflation and interest rates. I see a future not of constrained growth and half-hearted business investment, nor one handicapped by adverse terms of trade, but a future characterised by much lower interest rates, higher spending, less saving, more normal business investment, and maybe, a better export performance especially in the US market where UK manufactured goods have just received a price competitive boost thanks to President Trump. This will require the MPC to move beyond its current caution on interest rates, which are now falling, but too slowly. On this front, I am encouraged by the apparently reduced reliance on the Bank of England’s model to guide its policy decisions (as Ben Bernanke advised) and its apparent acceptance that high UK inflation is the product of “administered” price increases (tax, water, gas and electricity etc) that don’t have second round effects. Maybe the more obvious cooling in the labour market and falling wage settlements might also begin to influence the Committee at the next few meetings, as will its admission that high UK rates have reduced UK GDP by 2%.

At the start of this note, I asked if there was any escape. Unlike the aircrew in Joseph Heller’s brilliant but depressing book, I think there is, and it simply involves our policymakers doing the job they are charged with and focusing on a balanced, rational analysis of the economy’s future rather than the doom-laden but, in my view, flawed analysis of bodies like the National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) claims the UK faces a £50bn “black hole” that will require major tax rises or spending cuts. The media has largely repeated this without questioning its assumptions — namely its ultra-bearish forecast of UK growth averaging ~1.1% over the next four years, half the historic rate, driven by pessimistic views on investment, consumption, and exports.

By contrast, the OBR (and the Bank of England) forecast stronger growth, with tax receipts rising faster than spending from 2026/27. Under these projections, the deficit falls steadily to around 2% of GDP by 2029/30 and the current budget moves into surplus from 2027/28, meeting fiscal rules without large-scale tax hikes.

The danger is that alarmist forecasts, amplified by the media, will dent consumer and business confidence, creating the very slowdown they predict. A more rational approach would recognise falling interest rates, easing inflation pressures, and potential boosts to UK exports — particularly to the US — as reasons to expect stronger growth. The real risk is policymakers being led by headlines instead of balanced economic analysis.

If you want more than headlines — and analysis that challenges the lazy consensus — W4.0 is where you’ll find it. It's where I cut through the noise to focus on the facts that matter for the investment strategies I share there.

The media loves a “black hole” story. I prefer to dig into the numbers and tell you when the picture is better (or worse) than you’re being told.

For August only, we’re offering 4 months free on all annual plans — giving you a full year’s access for the price of eight months. You’ll get every strategy, update, and insight, plus the tools to create your own custom versions.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.