Brexit: A convenient and popular scapegoat

In my podcast from a couple of weeks ago, I mentioned a subject which, in the past, I have been very careful to avoid where possible, simply because it elicits such polarised and entrenched opinions. That subject is, of course, Brexit. Even now, over nine years after the vote and more than five since the UK left the EU, it still stirs extreme emotions, which were evident in the feedback I received from the podcast (you can watch the episode below if you haven't seen it).

Way back over ten years ago, in the lead-up to the vote, I was subjected to a lot of this very polarised debate when the business I was then a part of sought to provide its customers with independent economic analysis of the likely effects of Brexit. I judged at the time that the two sides of the debate were peddling such extreme nonsense about the costs and benefits of staying and leaving, and there was an urgent need for a more balanced, rational analysis of the two outcomes. The analysis (conducted by Capital Economics) was excellent in my humble opinion and was well received by the audience it was directed at. It concluded that the benefits of both staying and leaving, from an economic point of view, were trivial in comparison with other much more significant domestic economic challenges the UK confronted then and still does. In retrospect, most of the report’s conclusions were also absolutely correct, but because it satisfied neither side of the polarised debate at the time, it was criticised in the media and bizarrely interpreted as being both pro- and anti-Brexit. One well-known financial newspaper editor was particularly affronted by the report (I doubt he actually read it), and thereafter his publication adopted a very hostile stance towards both me and the business as a result.

Notably, the analysis conducted then and the opinions I expressed last week focused on the broad economic impact of Brexit, rather than the politics, diplomacy, or identity issues that are often embedded in the debate about the rights and wrongs of the decision the electorate made in 2016 (17.4 million people voted to leave, 51.9% of the 33.6 million votes cast). Additionally, the report and my views today are based on the impact of Brexit on the overall economy. At an individual company and sector level, there was clearly harm caused by the decision to leave, and I am acutely aware of some of these issues, not least because they severely impacted my own business at the time.

Having said that, I would like to clarify why I believe there is no obvious evidence of harm being inflicted on the UK economy by Brexit. In doing so, I also hope to highlight the reasons why it is used today by politicians and others as a convenient scapegoat for the economy’s ills.

Before delving into the evidence as I see it, I should point out that there is no definitive proof of harm or of no harm, and of course, there is no counterfactual to verify the conclusion. What there is, however, is evidence that I believe supports my contention and, by the same token, contradicts what Rachael Reeves and others in the government and in the OBR, apparently, have been saying recently about Brexit and its impact on the economy. (I think the OBR has once again been pontificating about Brexit and its impact on UK productivity, something which the OBR admits is at best an educated guess and which is based on data which the ONS is clearly having real problems accurately measuring.)

What’s the evidence?

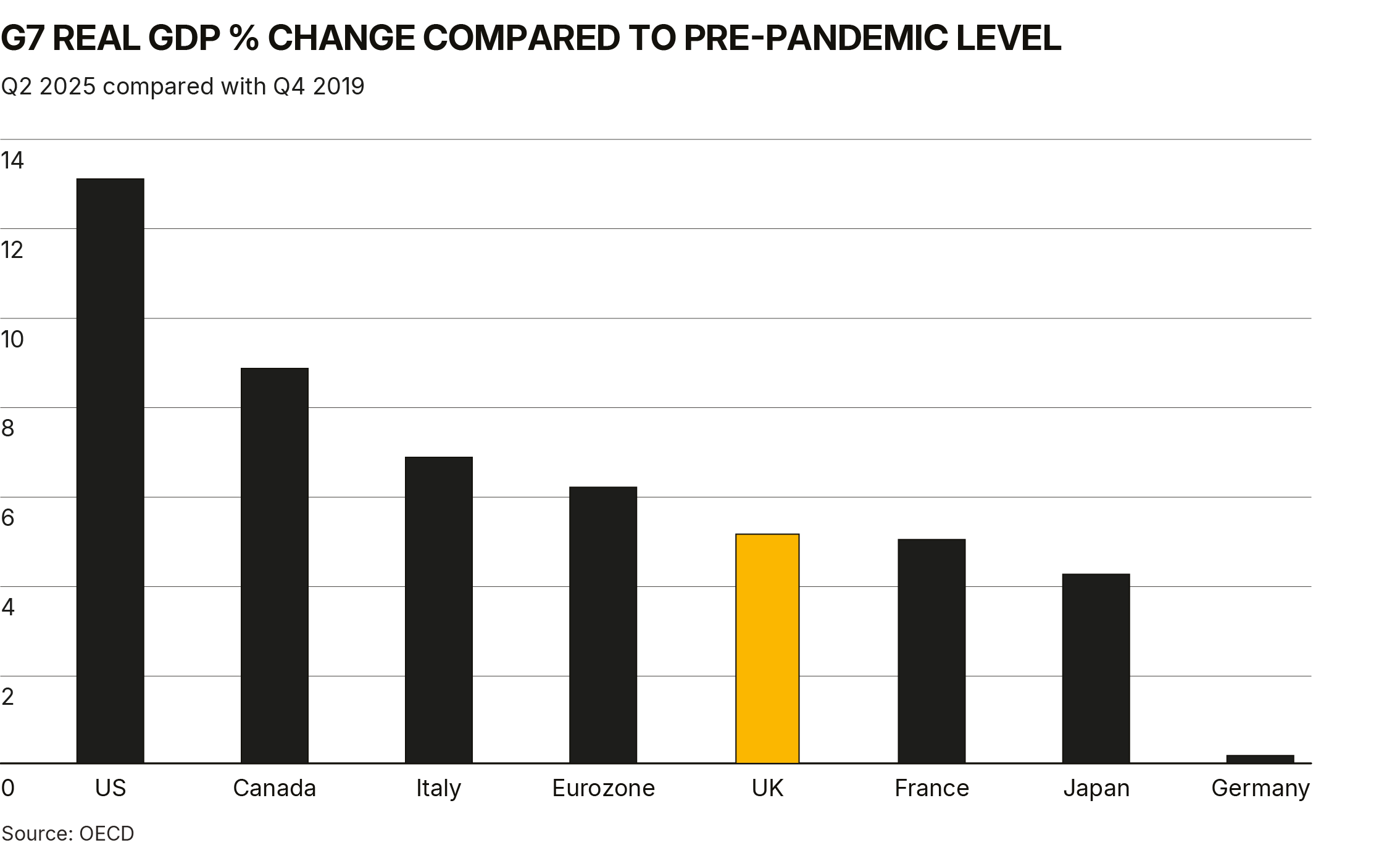

To start, I thought it would be helpful to present some headline macro growth data that compares the UK with other G7 countries and the EU. (OECD data) The chart illustrates the percentage change in GDP from the pre-pandemic level to the second quarter of 2025. In fact the average growth rate since the pandemic of both the EU and the UK is, as near as makes no difference 1% pa.

And for completeness, here’s some comparative data for the full year 2025.

So, whilst there is no counterfactual (what would have happened to the UK economy if it hadn’t left the EU), there doesn’t appear here, to be any tangible evidence of dramatic economic underperformance with peers, other than with the US and Canada, both of which had a very different approach to lockdowns during the pandemic. Indeed, the UK has outperformed its two nearest economic peers, France and Germany, over the past five years, and the gap appears to be widening.

And just in case anyone doubts that the UK had a much worse pandemic than other G7 economies, here is some evidence once again. What it shows is that the recession brought on by the pandemic and by the government’s reaction to it was much worse in the UK than across the G7. Clearly, a much steeper recession, caused by longer lockdowns and the constraints imposed on the UK economy at the time, created a significantly worse backdrop for the five-year comparisons of what happened in the period since the UK actually left the EU (31.1.2020), just before the pandemic hit.

Trade data

Drilling down into more detail, I examined trade data, which is where, if there were evidence of harm, one should most easily find it. After all, it was exports to the EU that were expected to suffer the most harm from the UK’s decision to leave. Indeed, basic AI enquiries about the damage caused by Brexit all come back with the claim that UK exports to the EU were what suffered the most from leaving the EU. To support the points I am about to make, I have used numerous charts, all sourced from the ONS, which we know has issues with data reliability. Unfortunately, there is no alternative data to examine.

The first chart below shows total UK goods and services exports (both EU and non-EU) over the period from 2014 to August 2025.

My observations are first, that the impact of the pandemic is clear in terms of the dramatic fall in exports of goods and services in 2020. Secondly, the data shows a more dramatic recovery and growth in 2021 and especially in 2022, in exports of both services and goods. That strong growth slowed in 2023 and 24, but growth appears to have picked up again in 2025, especially in services.

At this point, my observation is that if Brexit had created these trade headwinds, why did they dissipate in 2021 and 2022, and indeed more recently as well? My conclusion so far is that it looks very much as if the pandemic caused the slump in exports and the return to normality in 2021 and 2022 saw both a recovery and a resumption of the trend growth seen before COVID struck.

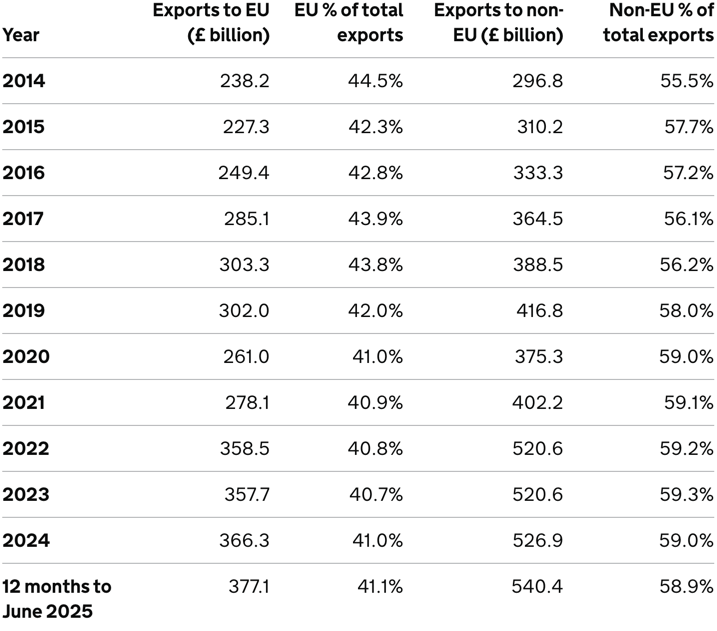

When looking at the same data (see table below), split between exports to the EU and non-EU countries, it is once again difficult to conclude that Brexit caused the problems in 2020. If that were so, what explains the strong growth in EU goods exports, for example, in 2021 and 2022?

Once again, when investigating the so-called damage done by Brexit, the most frequently cited evidence is the decline in the UK’s exports to the EU as a proportion of total exports. Once again, I think this is bogus, for a number of reasons.

- The EU has grown more slowly than the rest of the world over this period. Faster economic growth in non-EU countries should be reflected in faster-growing exports to them.

- The US is the UK’s single most important export market by a long way. Its economy has grown much faster over this period than that of the EU, and so it should have taken a greater share of the UK’s exports.

- When the consensus makes this point, it uses data that significantly pre-dates the UK’s exit from the EU. If we examine data from just before the UK left the EU (2019), you can see from the table below that the decline in the EU’s share of total UK exports is marginal, and consequently, the growth in non-EU exports is equally small.

Source: ONS

But, drilling into a bit more detail, this argument completely falls away. In summary, it’s completely wrong. Critics of Brexit have maintained that the extra burden of paperwork and customs checks, etc, along with additional trade barriers, would mean that leaving the EU would have a more pronounced effect on the UK’s goods exports than its effects on service exports. Someone making this argument (and most commentators do, along with Rachael Reeves, etc) would presumably cite the falling proportion of goods exports to the EU as a % of total goods exports as evidence of this harm. Unfortunately for them, however, that is not what the evidence shows. In fact, bizarrely, the proportion of goods exports accounted for by the EU has actually GONE UP since 2019, as shown in the table below, from 46.1% to 47% in the twelve months to August 2025.

Source: ONS

Clearly, the fall that everyone is talking about pre-dated the UK’s exit from the EU. In fact, it even predated the Brexit vote, as can be seen in the data from 2014 to 2015, when the proportion fell from 50.9% to 47.2%.

In summary, the proportion of the UK’s goods exports to the EU, which, according to consensus, would be most harmed by the UK leaving, has remained the same since 2015. In other words, this argument about the harm caused by Brexit is basically bollocks. Put another way, goods exports from the UK to the EU have actually outperformed goods exports to non-EU countries since the UK left the EU.

Services

To complete the picture, I should also focus on services which have now become a more important and faster-growing proportion of total UK exports. Here, the data is also very revealing.

This first chart illustrates the significant growth in services exports over the last eleven years. The dip that occurred during the pandemic was shallower than that seen in goods exports, and the growth since has been very strong.

Fundamentally, these data reflect significant underlying changes in the structure of the UK economy, as manufacturing (both for domestic markets and exports) has continued to decline as a proportion of the economy, from just over 14% in 2014 to about 8% today, while the service sector has seen a corresponding increase. These shifts have naturally also been reflected in UK export data. However, interestingly, and most pertinent to the argument I am addressing in this blog, there is absolutely no evidence in the data of the supposed harm done to services exports to the EU post-Brexit. Indeed, as you can see in the table below, the proportion of services exports to the EU as a % of total services exports has remained static over the last eleven years at 37%. So, put another way, the growth in services exports to the EU has kept in lock step with growth in services exports to non-EU countries.

Source: ONS

Conclusions

Before I make the final points, I should reiterate that these data are, by their nature, aggregate. They do not reflect the fact that Brexit undoubtedly harmed individual businesses and certain sectors; however, in totality, there is absolutely no evidence in the data I am examining to support the widely accepted and promoted idea that Brexit caused harm to the UK economy. Indeed, in the very sector where there should be the most obvious evidence of this so-called harm, there is none. None at all. Quite the reverse, in the most sensitive sector of all, manufacturing exports to the EU, there is clear evidence that these exports have outperformed exports to non-EU destinations since 2019.

So why does this narrative exist when the evidence is contradictory? One obvious answer is that the market for economic facts is very thin. All too often, consensus economic commentary is accepted without question, and once established, narratives become “fact”.

It’s also the case that, aside from Brexit’s supposed impact on trade, today’s politicians will also be looking to blame Brexit for the UK’s poor performance on productivity. As I have highlighted in recent blogs, productivity data should be handled with extreme care. The ONS itself has little confidence in the data it produces on output and employment, which are the raw material for productivity calculations, and furthermore, the OBR, which, as I have said, would struggle to forecast Christmas, itself says that its productivity forecasts are at best, uneducated educated guesses. But despite this ludicrous situation, it appears that the OBR’s downgraded UK productivity forecasts for the period from November through to the end of the decade will, according to the media, be used to justify lower economic growth forecasts over the same period and on which will be based decisions on how much taxes need to rise in the budget.

If this is true, and I have doubts about this storyline as I have indicated in recent blogs, then it might suit a Chancellor struggling politically with yet another tax-raising budget, to blame something that she wasn’t responsible for and indeed opposed, namely Brexit. The truth, however, is once again rather different.

The UK economy was clearly damaged by the pandemic, and in particular, by the government's bungled handling of it. The opposition at the time, of which the Chancellor was a part, advocated for longer lockdowns and more restrictions, which, if heeded, would have inflicted even greater harm on the economy. It is also the case that the Ukraine war caused a lot of harm, too. It cost the UK government about £50bn in total (the cost of schemes to protect households from the worst effects of the cost-of-living crisis), but in addition, the massive increases in energy prices that followed the invasion of Ukraine, led to a dramatic rise in inflation and interest rates, the legacy of which we are still enduring nearly four years on. It is these events that have caused obvious harm to the UK economy and from which, in my view, we are finally recovering.

Brexit’s economic impact, which I cannot detect in the data where it should be most evident, is trivial, especially in relation to these two seismic events. Interestingly, this is pretty much what the report I referred to earlier in this piece concluded nearly ten years ago. I don’t doubt that many will highlight Brexit’s impact on politics, the UK’s standing in the world, its impact on diplomatic relations with our nearest neighbours and other similar related issues, but these are not ones I am talking about here.

To conclude, I cannot accept the consensus claim that Brexit caused damage to the economy or, more precisely, to the UK’s trading performance and to productivity, simply because there is no evidence to support that claim—absolutely none.

I’ve tended to avoid Brexit because it provokes more emotion than reason, but it’s now being used as an easy excuse for Britain’s economic ills. The Chancellor and the OBR claim Brexit has harmed productivity and trade — yet the evidence says otherwise.

Look at the facts. Since leaving the EU, the UK has grown faster than France and Germany, despite experiencing a much deeper recession during the pandemic. On trade, total exports have risen strongly. The supposed collapse in EU trade simply didn’t happen — in fact, the EU’s share of UK goods exports has increased slightly since 2019, from 46.1% to 47%. Services exports, which now dominate our economy, have also grown robustly, with EU demand keeping pace with non-EU markets.

If Brexit were truly the problem, this data would look very different. What actually hurt the economy were two far greater shocks: the government’s mishandling of the pandemic and the energy crisis triggered by the Ukraine war. Those events caused the inflation surge, higher interest rates and the fiscal strain we’re still dealing with today.

So why does the “Brexit damage” story persist? Because it’s politically useful. It spares today’s government from admitting that excessive spending, poor productivity measurement, and flawed OBR forecasts — not Brexit — are the real issues.

Almost ten years on, the reality remains as it was then: Brexit’s economic impact is trivial compared with the forces that really shaped the UK’s recent fortunes. The data don’t show decline — they show resilience.

Related posts

Introducing W4.0

Direct access to Neil Woodford’s proven investment strategies.

Subscribe to receive Woodford Views in your Inbox

Subscribe for insightful analysis that breaks free from mainstream narratives.